Steven Frears is going to make a film about Billy Wilder, Han-Joon Chang confesses that One Hundred Years of Solitude is his favorite novel, and Carlos Franganillo argues that we tend to idealize the past… All this at the Hay Festival Seville 2024.

Story

Steven Frears is going to make a film about Billy Wilder, Han-Joon Chang confesses that One Hundred Years of Solitude is his favorite novel, and Carlos Franganillo argues that we tend to idealize the past… All this at the Hay Festival Seville 2024.

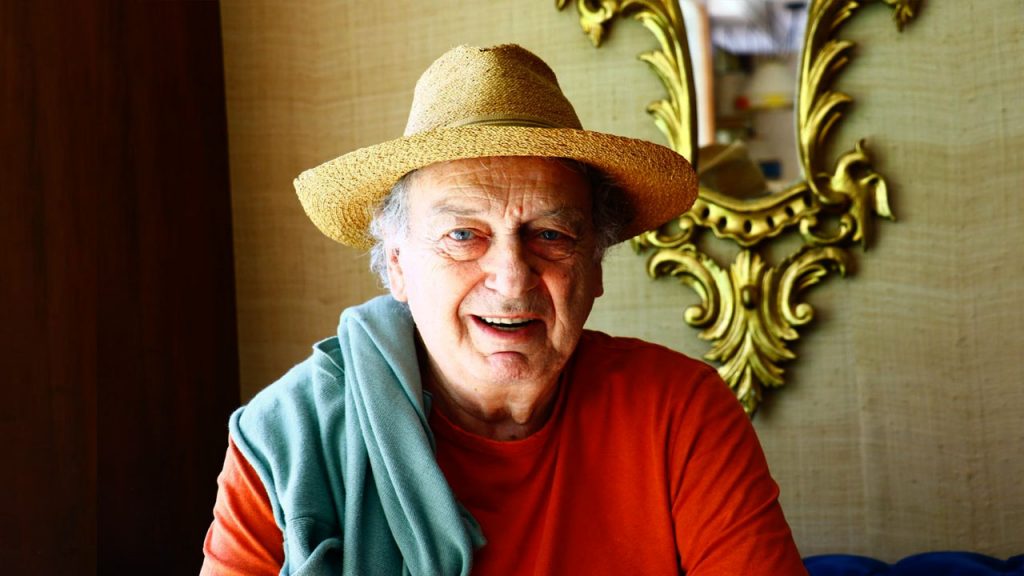

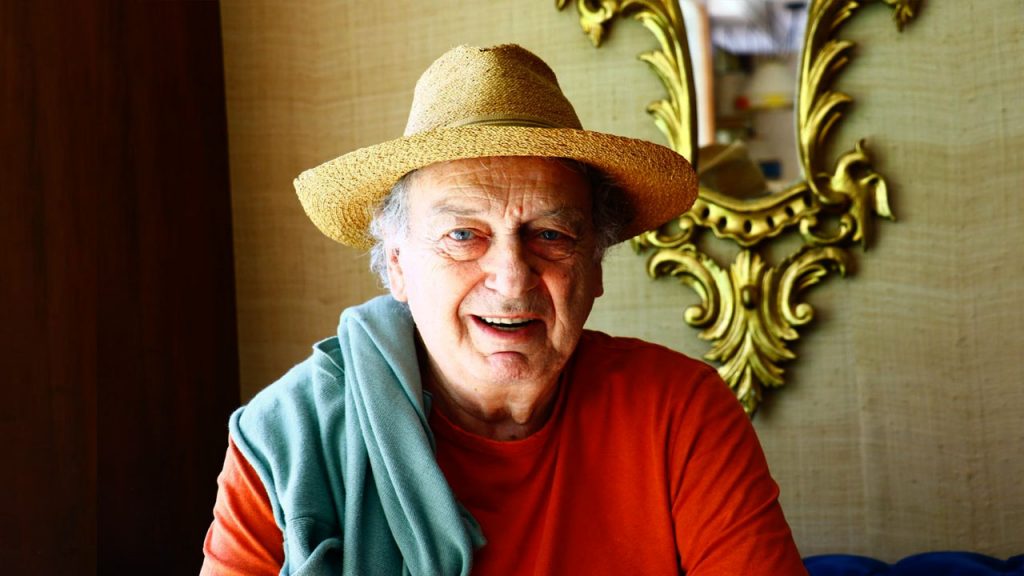

I’ve just finished reading The Life and Death of Émile Ajar, by and about one of my favorite writers, or should I say two of my favorite writers: Émile Ajar was one of Gary’s many aliases, which is how he managed to break the Goncourt Prize rule that it can’t be awarded to the same writer twice, after winning it first in 1956 with Roots of Heaven, and then again as Émile Ajar with Life Before Him in 1975.

Born in 1914, by his sixties, and with a distinguished literary career behind him, Romain Gary simply got tired of being himself, unhappy with the image the public and the intelligentsia had bestowed on him, and more specifically by the all-seeing, all-knowing Jean-Paul Sartre’s comment that it would take 30 years to find out whether Gary’s 1945 A European Education was the best novel about La Résistance or not. Gary was not about to accept that he was finished.

He was fed up with people describing his various lives as an aviator, diplomat, writer, polyglot, as symbols of a full life, when he simply saw himself as an adventurer, driven by an irresistible lust for life. “The truth is that I was deeply touched by man’s oldest temptation: the multiplicity of Prometheus,” he wrote in The Life and Death of Émile Ajar.

So he reinvented himself again, convincing a friend to send the manuscripts of a certain Émile Ajar to the Gallimard publishing house. He wrote four novels under this pseudonym, and one of them won him the Goncourt again, the jury unaware of Ajar’s true identity. Other nom de plumes included Fosco Sinibaldi and Shatan Bogat, along with his real name, Roman Kascew.

There’s no point in discussing Sartre’s opinion of A European Education, but there is no denying that Gary’s The Kites is not only one of the best books about the Second World War, it is also an unforgettably bitter-sweet love story, perhaps drawing on his time married to Jean Seberg, mother of his only son.

Both lives ended tragically. Seberg committed suicide in 1979 at the age of 41. She was found dead in Paris in her car with a note in her hand, addressed to her only son, Diego: “Dear Diego: I can’t stand the pressure anymore. Forgive me. Be strong.” Her support for the Black Panther movement had angered the FBI, which for more than a decade had put all its efforts into making her life impossible.

A few months later, at the age of 66, Romain Gary blew his brains out with a Smith & Wesson. “Anybody who has created himself has the right to destroy himself,” wrote Nuria Barrios in 2008. With Gary died a host of other writers: Roman Kacew, Shatan Bogat, Fosco Sinibaldi, and of course Émile Ajar. “What no one knows is which of them pulled the trigger,” concludes Barrios, who has just published Todo arde, a powerful reworking of the myth of Orpheus set in Madrid’s drug underworld.

I have to say, having read the works of most of Gary’s alter egos, I still don’t know which is my favorite.

We can’t avoid acting in accordance with plans, after all, a plan provides security and reduces our degree of uncertainty to tolerable levels. That said, it’s also nice to forget the plan and allow life to surprise us, because a surprise can often give us that vital hit we were hoping for or simply lift us out of our planned boredom.

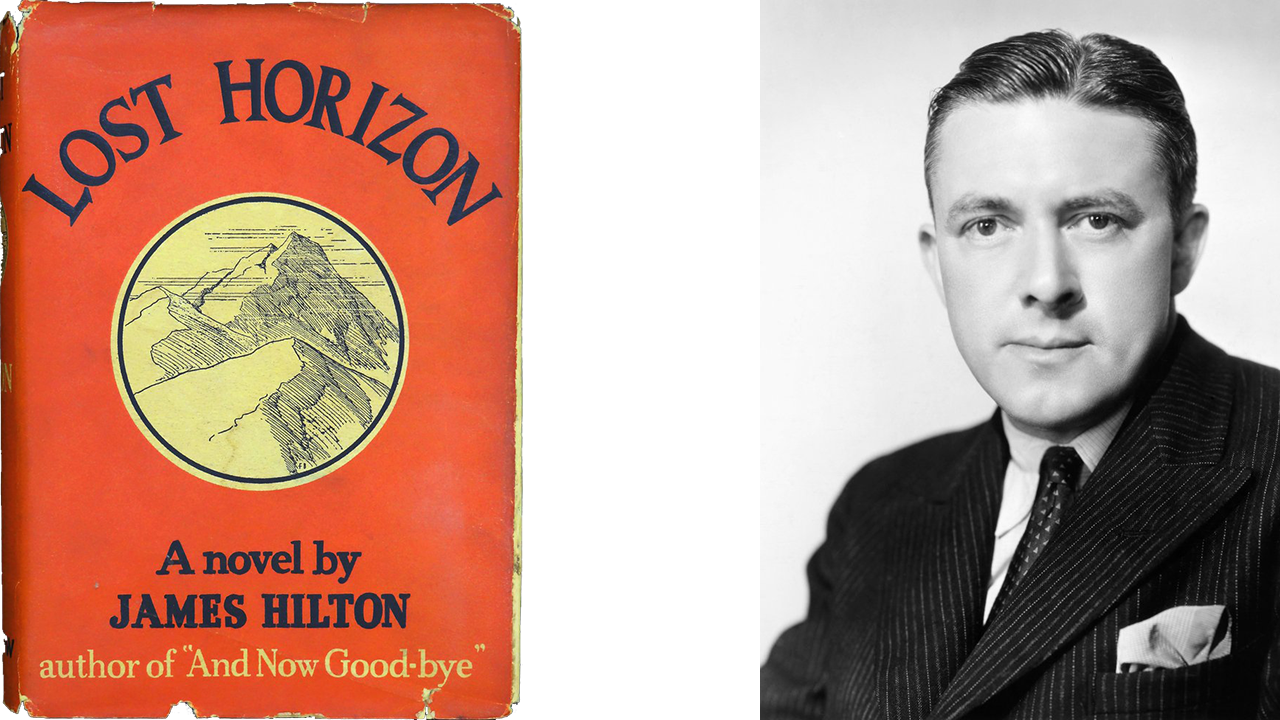

I say this because flying between Beijing and Shanghai last week, I picked up a copy of the China Daily and half-heartedly began to scan its pages. When I opened it, I came across a great article called Where is Shangri-La? by Simon Chapman and DJ Clark about one of my favorite books, Lost Horizon, by the writer and prolific smoker James Hilton, who was born in 1900 and died at the early age of 54.

Needless to say, Lost Horizon, published in 1933 and an immediate international best-seller, is the origin of the term Shangri-La, a fictional Tibetan utopia that has not only captured the western imagination, along with other mythical places such as El Dorado and Xanadu, but also lends its name to an international hotel chain. Any number of communities have claimed to be the origin of the paradise Hilton invented (incidentally, he never visited the region), among them, Lijiang, Zhongdian, both in China’s Yunnan province. Shangri-La in Chinese is written 香格里拉 (Xianggelila).

Chapman and Clark focus on the question of why Hilton never admitted that the earthly paradise in his book was based on a series of articles written by the Austrian Joseph Rock published in the National Geographic, while accepting the lesser influence of Father Évariste Régis Huc.

I’ll leave you with the beginning of the novel, as said, one of my favorites, which is nothing more nor less than a great story well told: “Cigars had burned low, and we were beginning to sample the disillusionment that usually afflicts old school friends who have met again as men and found themselves with less in common than they had believed they had…

On a day like today, November 21, but in 1898, René Magritte was born. In his honor, a few lines and this video, in which I link his famous “This is not a pipe” with Diderot and our book, Dibugrafías.

This is not a story

René Magritte spoke about how images deceive. Of his famous painting, «Ceci n’est pas une pipe» (This is not a pipe), he said: «The famous pipe. How people reproached me! And yet, could you fill my pipe? No, it’s just a representation… So if I had written on my picture ‘This is a pipe’, I’d have been lying…» Long before Magritte, Diderot said «This is not a story». Words deceive as much as images do. Liberty, happiness or justice are also merely representations we fill as we see fit. So who’s lying?

隋唐演义150-001

Nothing is more important than telling a tale, or to put it another way, nothing is more important than living to tell a tale. Once the tale is over, the party, sometimes great fun, sometimes very sad, is also inevitably over.

Last September 11, Shan Tianfang (单田芳), like the unfortunate occupants of the Twin Towers years earlier, ceased telling tales.Shan Tianfang was one of the greatest modern exponents, if not the greatest, of what the Chinese call Pingshu (评书 or shuoshu 说书), the oral storytelling tradition dating to the Song dynasty (960 – 1279). In his memory, I leave this small example of his art: Shan Tianfang, a Superstar of Chinese Storytelling