Slowly agitated by chance, As Slow As Possible by Kit Fang and Agitación by Jorge Freire make a perfect mix in explaining why this world is so troubled (La Geografía del erizo).

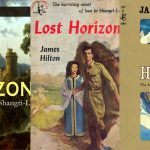

If pressed, I would probably venture that chance was responsible for the recent appearance on my desk of two books, which while from different genres and perspectives, want the same thing: a slow and careful explanation of why this world is so troubled. This may not be the occasion to point out that nothing happens by chance (nihil fit casu in mundo), but nevertheless, that’s exactly what I’m going to do.

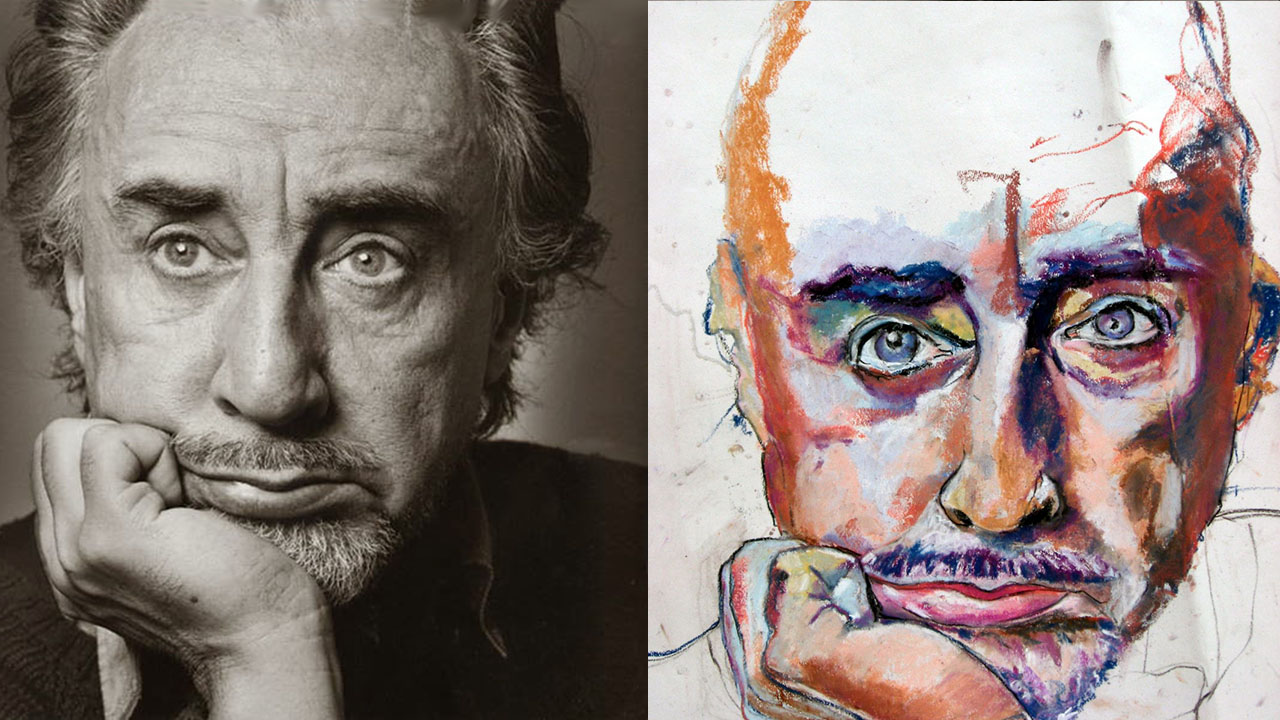

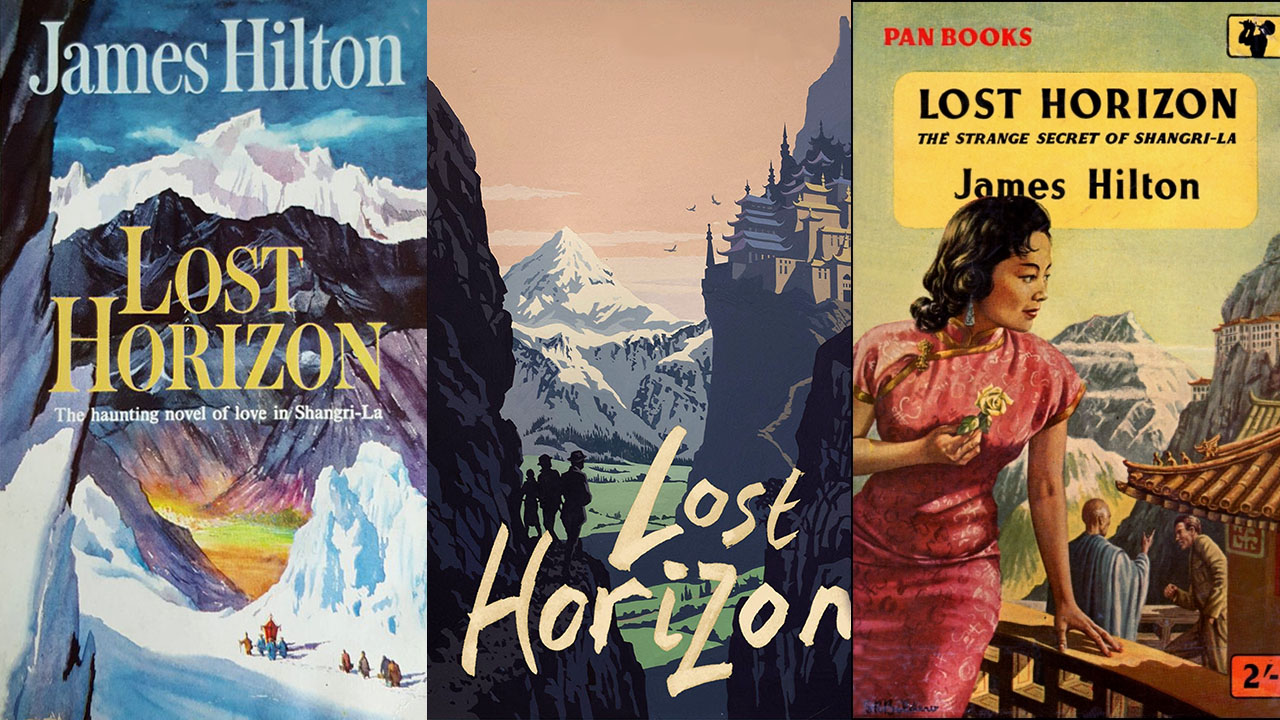

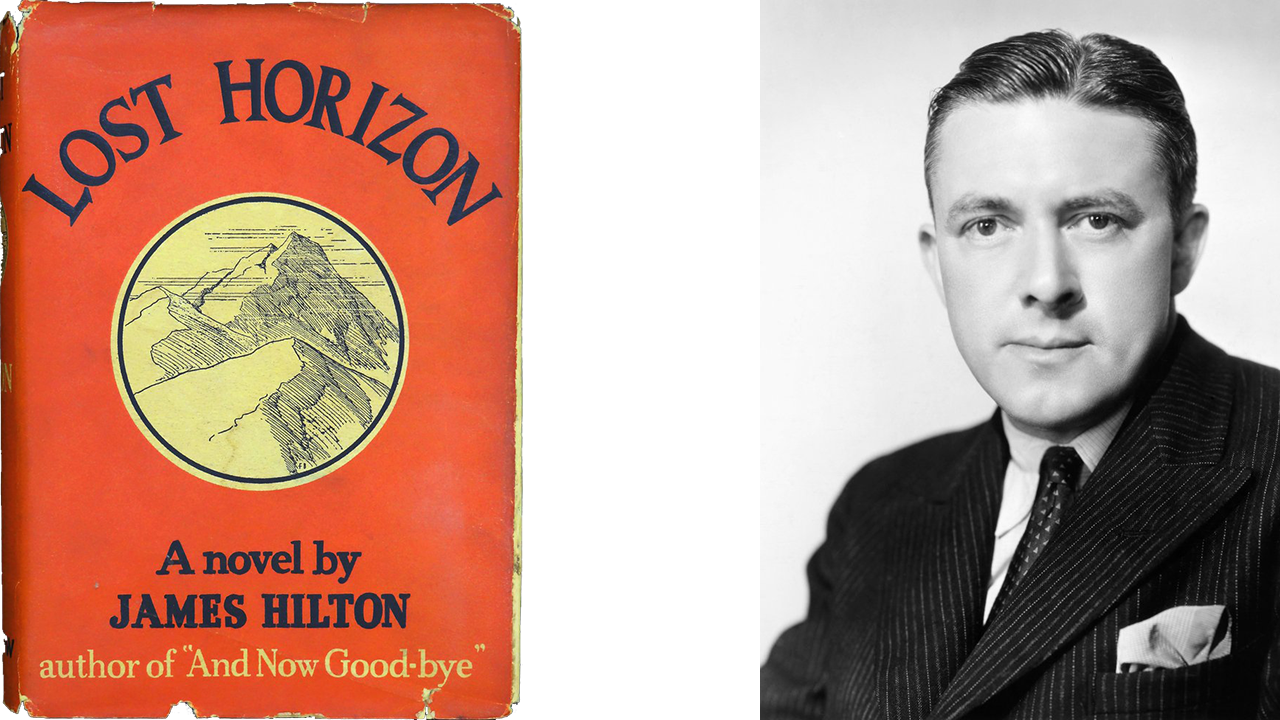

The first is As Slow As Possible, a collection of poems by the award-winning Hong Kong poet Kit Fan. I met Kit Fan online last month, at the IE Foundation’s Prizes in the Humanities, and his way of speaking immediately aroused my curiosity about his work.

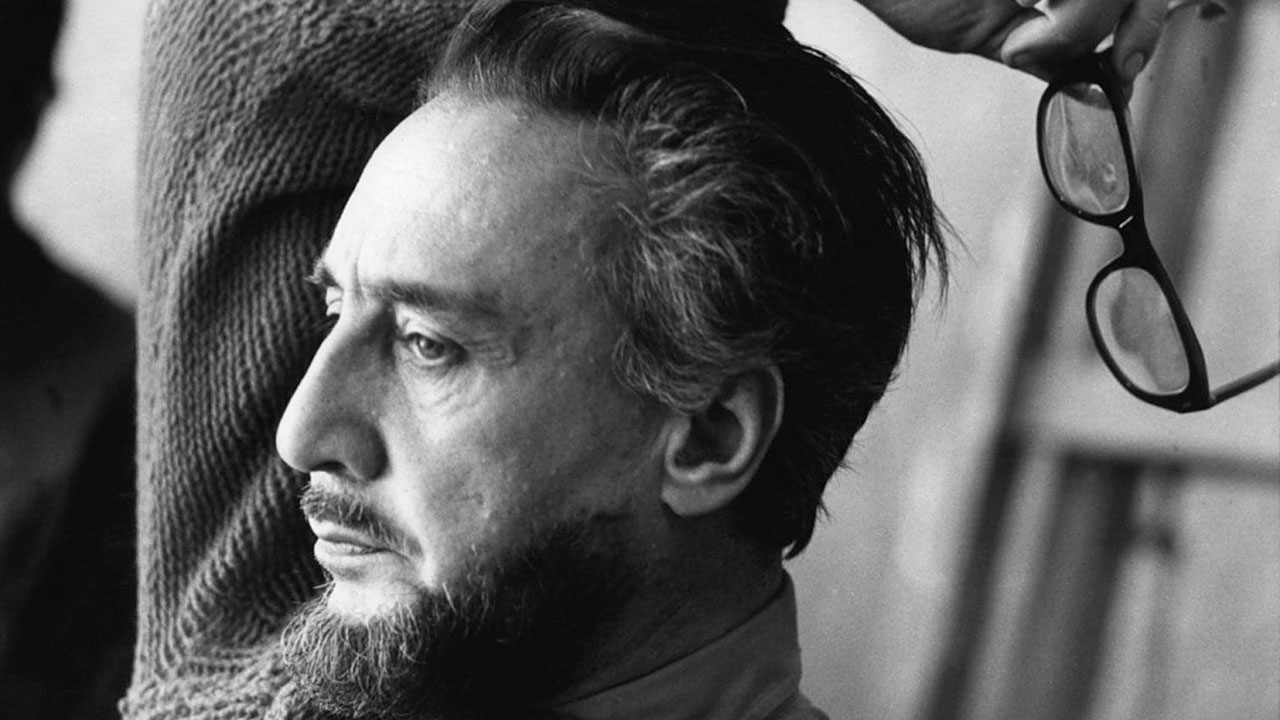

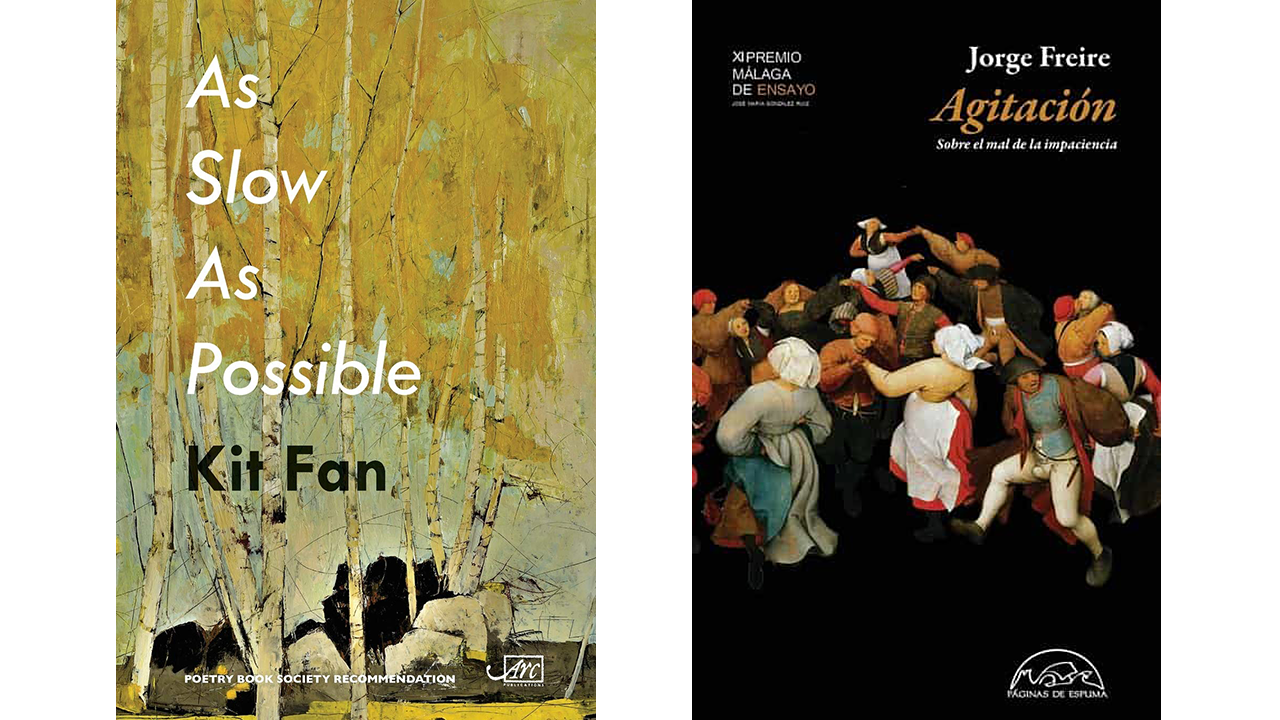

The second is an essay entitled Agitación by Jorge Freire. Santander-based lawyer Pilar de la Hera, recommended the award-winning philosopher from Madrid last weekend. By the way, Pilar took part in Spain’s first post-lockdown case by videoconference, as The New York Times’ Raphael Minder writes in Spain’s Courts, Already Strained, Face Crisis as Lockdown Lifts.

When I say that both books want the same thing, I mean that they both want to provide a space for reflection in this runaway world, one in which we not only run incessantly, like hamsters in a wheel, but also forget that There was a time when we were not here, as one of his poems reminds us.

We would do well to remember the words of the Buddhist poet Hanshan, written 1200 years ago: we humans live in blinding dust, like insects in a bowl. All day w go around and around and never get out of the bowl (人生在塵蒙 恰似盆中蟲 終日行繞繞 不離其盆中).

Fan writes from his guts, slowly, driven by the fire in his heart, tempered by the power of his words and intellect. I was captivated by how As Slow As Possible brings together, slowly, steadily, personalities from Eastern and Western culture, ranging from Zurbarán to apocryphal haikus attributed to the enigmatic Chinese painter Fan Kuan (范寬, 960-1030), and on to Brueghel, Banksy, and Sancho Panza (the latter is ironically quoted in the poem Don Kowloon).

In contrast, Freire embarks on a frenetic race of quotes and references, illustrating how the epidemic of agitation, the disease of our era, not only swallows up our entire life thanks to the adrenaline we create (running, being Zen, vegan, rafting in Indonesia…), but also any kind of cultural product at our disposal. When we become agitated we move, but we don’t advance,” he argues. All this agitation seems rooted in our horror of the home. (La grande maladie de l’horreur du domicile diagnosed by Baudelaire).

In short, if, by chance you’ve taken the time to read this text, I can only hope that my words have been sufficient to lure you to explore these two magnificent books slowly and carefully.