Surely one of the most difficult challenges we face each day is simply presenting things as they are, without our perception of them getting in the way. It’s pretty much the same with writing style. There was a time when I loved recognizing the penmanship of a text’s author. It’s Proust writing, this is Scott Fitzgerald, no, Hemingway… But these days, I find myself appreciating what is being said much more than enjoying any clues as to who is saying it. My judgment would be that this is a form of transparent justice with respect to the written object.

I say this in light of Ruskinland, recently published by Financial Times journalist Andrew Hill, who expresses to perfection my thoughts above. His goal in the book is to make us see why the thinking of John Ruskin (who I called The Napoleon of Brantwood) is still needed today (page 26), and throughout the book it’s as though Ruskin himself were speaking to us, when evidently this is not the case. Ruskinland is the perfect enticement to read Ruskin. What more could one ask for?

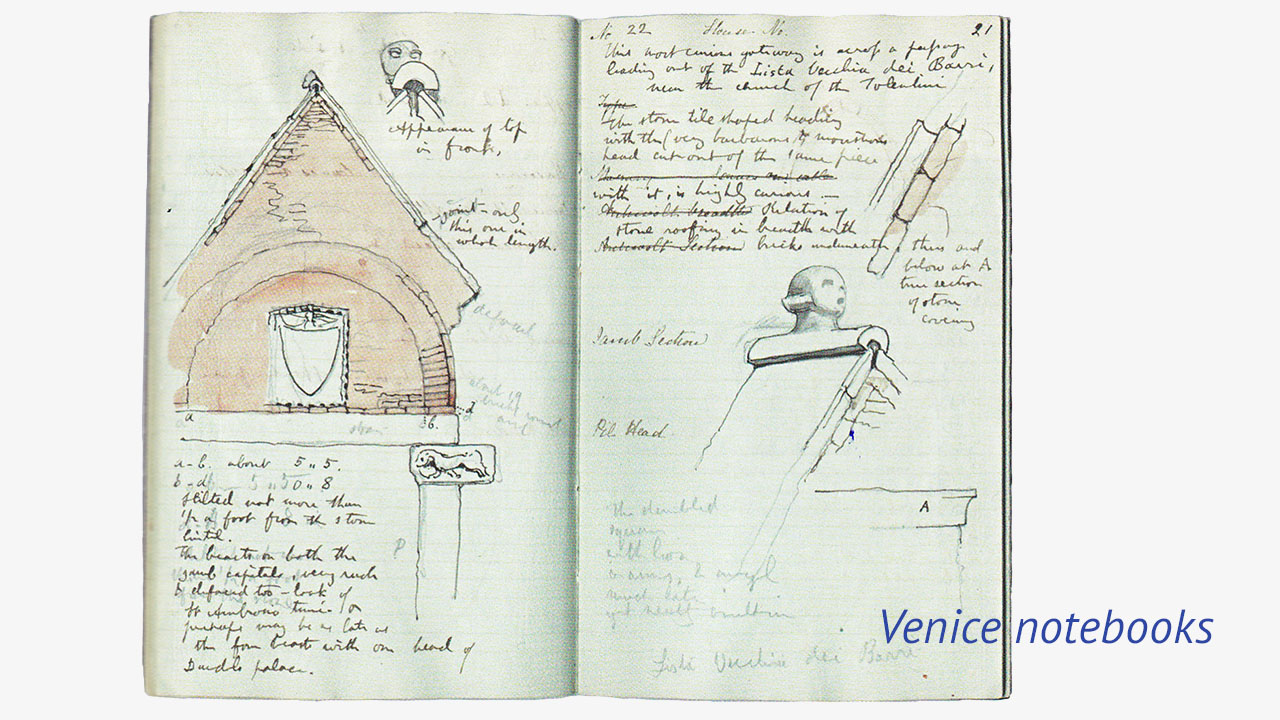

In short, I recommend the book wholeheartedly, and would advise anybody who says they don’t have the time to do so to start with the third chapter, Seeing, which discusses Ruskin’s passion for simply watching: he was capable of looking at an object or landscape for hours on end, trying to make sure he hadn’t overlooked any aspect of it. The opening lines of the chapter quote Ruskin on the importance of taking the time to look:

The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something, and tell what it saw in a plain way. Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands think for one who can see.

To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion, all in one.

PS: In October 2017, while still ignorant of Ruskin’s work, I published a collection of stories called Dibugrafías with the painter Miguel Panadero. One of them, Escalenes, discusses the virtue of seeing clearly in the dark. I leave it with you in the hope it clears a few things up…!!!

Scalenes

A triangulated head is clearly a mystery, because the number three has always been a mystery.

A triangulated head is clearly a mystery, because the number three has always been a mystery.

Let’s take a closer look:

If the three sides of a triangle are equal, we call it an equilateral triangle. The triangle is isosceles if only two of the sides are equal. And it is scalene if all three sides are unequal. Everybody knows, however, that these are just the certainties of geometry, because in the world out there, everything is unequal, scalene, and that’s without bringing heads into it. Now things seem a little clearer.

The virtue of being able to see clearly in the dark seems more like a virtue of geometry; let’s face it, not all heads are of equal capacity, but still none of them see clearly. Or does anybody know of a head that can see beyond the darkness?

If we move on from geometry to arithmetic, we have addition. The addition of a head, plus another head, and another, might this help gain clarity?

Marbella, May 1, 2014