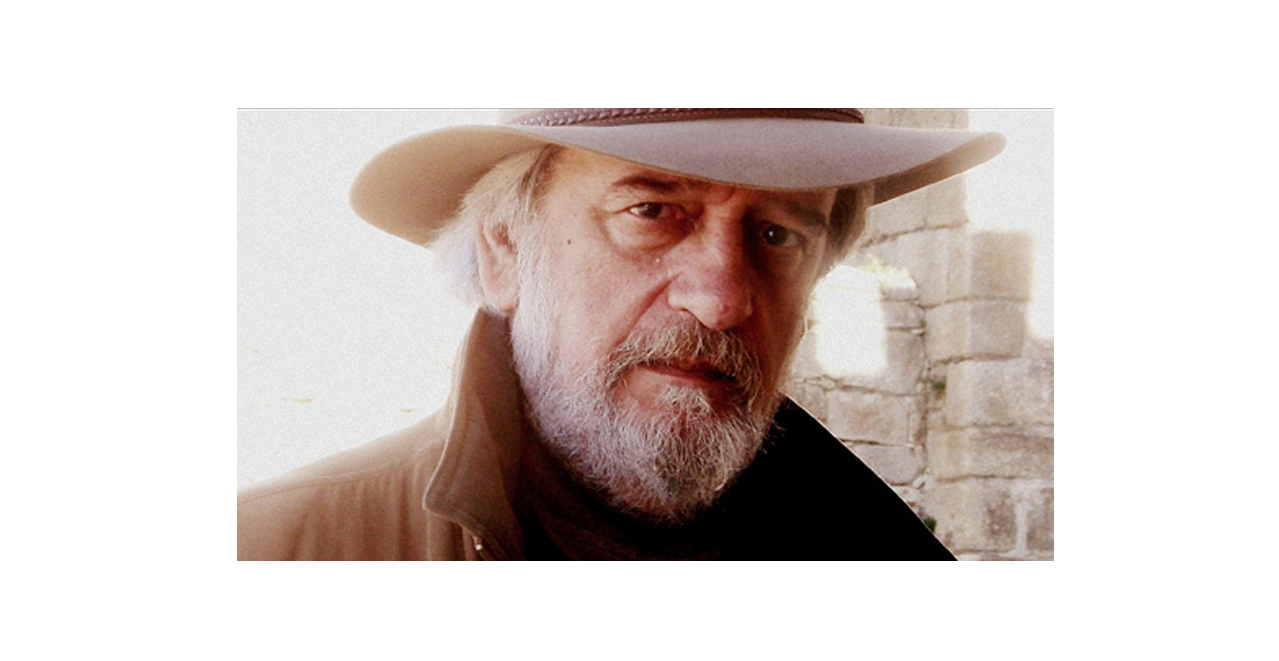

Enrique Gracia Trinidad pays homage to Whitman, Celaya, Lorca, and more.

Enrique Gracia Trinidad’s “Desconcertada agenda” (Cuadernos de Laberinto) has been my companion since it was published in October of last year. This collection of poetry reaches into the soul, and came knocking on my door, on one of those doors we leave open to allow fresh air in.

For some time now, I have paid tribute to everything that fights the whiff of origin, the crack through which the nationalist pestilence sneaks in, which inoculates the germ of greatness, that a country will be great again, that is once again infecting the world. And I pay an even greater tribute, if possible, when I come across something so well said, as is the case with each of the poems in this collection.

Gracia Trinidad begins, as we all do, with what surrounds him. Twenty poems are grouped in a first part, entitled “My Madrid“, the city where he was born. This is an excerpt from the first poem I read, where he elegantly vaccinates himself against the aforementioned germ, discovering the world under his skin.

Distant

I’m Greek and I’m Roman, also Carthaginian.

I carry in my hands the skin of Sephardim

of Umayyad Arabs in Al-Andalus.

…

When I laugh I discover on my cheeks

the cold breath of northern barbarians.

I know there’s Africa in me, even if it’s distant.

…

If I lost my black skin it was because so many centuries

had dilutedit

and the same thing happened with other skins

that I once had in Samarkand,

on the island of Hokkaido, on Rapa Nui,

or in the Loltun cave in Yucatan.

When I was born in Madrid my soul was already old,

multicolored, diffuse and perfected.

All time rests in my throat

every blood sleeps in my blood

and they all know me

and I recognize them.

(THE CURVE OF AVENIDA DE LOS TOREROS, MADRID, JUNE 2020)

In the second part, these poems are joined by another twenty entitled “So far and so close“, through which the world transits via the gates that the poet has opened. “In the realm of passage and wonder, a gate always awaits. It doesn’t matter how it looks at us, it doesn’t matter what its name is, it doesn’t matter if it prevents us from passing or invites us.” Sarcastically, at the end, he confesses that he prefers a small door with a cat flap.

A heavy work load prevented me from attending the launch of the book. Perhaps, if I had, I would have put it aside by adding it to the list of books to read, which the Japanese call tsundoku (積ん読). Chi lo sa? What I do know is that it has been a pleasure to read it calmly over the past few months. I’m not going to outline Gracia Trinidad’s long career here, but I will insist when something is worth reading. There’s “Doble juego” written with Raquel Lanseros and a prologue by Luis Alberto de Cuenca; “Nada para después“, and one that I haven’t been able to get my hands on yet, despite my interest in all things Chinese: “Cantos de amor y de ausencia” by Xu Zonghui and Gracia Trinidad, which brings together cí (词) from 15 classical Chinese poets who lived between the ninth and twelfth centuries.

We must continue opening gates, because “gates have souls, and although other doors are hollows, lintels, jambs or tympanums, but no one closes them, they are arches of remembrance whose merits are questionable: Brandenburg, Alcalá, Medinaceli, Rome, Palmyra…“But there’s a limit to everything,” he reveals:

«When I push the gate at the end

No one will be able to sell me colorful balloons.»

I like my companion, so I will not totally perish and much of me will survive (Non omnis moriar) at 200 km per hour, and instead slowly. “And if there’s still something left,” Gracia Trinidad entitles a poem in memory of León Felipe:

“All that, which is hardly anything,

but it might as well be all

it must be without a doubt

poetry.”

P.S.: Horace forever!:«Non omnis moriar multaque pars mei vitabit Libitinam», Odes III, 30, 6-7. And if a Roman didn’t say it, a Greek would have, or even one of those super Chinese!!