If you don’t know BTS, Parasites or The squid game you have probably been living under a rock. You have to ride the Korean wave (Hallyu).

Afghan graffiti artist Shamsia Hassani takes on the Taliban.

The Year of the Ox. According to Chinese astrology, as well as others, our destiny is directly related to the position of the planets at the time of our birth. Chinese astrologers, observing the orbit of Jupiter around the sun, divided it into 12 sections, corresponding to 12 years, each named after an animal.

The Canarian Garoé tree was believed by some to be sacred, filled with water, it would cry for scorned lovers. Others believe the Teide bird to be the most beautiful of its kind, which nests inside the volcano of the same name, as black as the blackbird, so black that it is blue, while the song says that it is the second star on the right, the path that leads to the island that does not exist (L’isola che non c’è), just as it leads us to see that tree, and that bird, which has only flown in the verses of poets. Everything is magua, melancholy, the feeling of the islands in the magnificent Journey to the Canary Islands, a sentimental portrait of our islands that Juan Cruz wrote at the suggestion of the late Peter Mayer.

Today, a travel book seems anachronistic, almost dystopian. But a book of travels, or of something else, is the story of a horizon, of a hope, and tells of a way of seeing things. And as we travel through life, the question is always how we continue that journey, for which the story of other lives and other journeys, helps. I understand then that we must seek hope to continue living, says Cruz, citing the Canarian poet José Luis Pernas.

I would never have imagined myself reading a book like this in late July. However, it seduced me, just like the Rafael Alberti bookstore in Madrid, where I went for my weekly hit of dopamine from Lola Larumbe. But instead, I ran into Juan Cruz, who had just arrived to sign books. An encounter between Canarians in the land of the Goths, far from the fish tank of the archipelago, aroused the camaraderie that all encounters do between outsiders who are far from home.

I told him that during lockdown I had met Lola Larumbe by chance one Saturday, out looking for tobacco, and seeing movement from within the closed bookstore, I knocked on the door, only to be politely told the shop was closed to customers. But when I told her that I simply wanted a book of poetry, whichever she thought best, she selected one, and since then I have gone back, to be there again, like the poem Volver from Eloy Sánchez Rosillo’s Confidencias, the book she initially chose.

-Well, I can recommend this book – from the only poet who made Vargas Llosa cry, offered Juan Cruz.

-No, thanks,” I said, ignoring the book he was showing me. I want something recommended by that lady over there. Lola Larumbe, whose name I still didn’t know at the time, had just appeared at the back of the bookstore. And amid the laughter, she asked me mine.

That day, from the many books that Cruz was due to sign, I chose Journey to the Canary Islands, over the course of which, he explores what the islands are, and what they have been and inspired by. The reader is grateful he avoids the affectation of so many, if not all, of referring to Gabriel García Márquez as Gabo. That said, in balance, what’s missing among so many fine literary allusions are some quotes by women, such as Cruz’s prodigious fellow Canarian Mercedes Pinto Armas de la Rosa y Clós, whose novel, El (Him), was made into a film of the same name by Luis Buñuel in 1953. Thirty years earlier, during the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, she gave a lecture in Madrid entitled Divorce as a hygienic measure. She went into exile, as did Miguel de Unamuno, whom Cruz, along with Aldecoa, Humboldt, Breton, and so many others, does cite at every opportunity.

Pablo Neruda, who was deeply impressed by her, wrote the words below during her lifetime, and which were put on her tombstone after she died in 1976.

Mercedes Pinto lives in the wind of the storm.

With her heart facing the air.

Energetically alone. Urgently alive.

Sure of successes and invocations.

Fearful and kind in her tragic garment of light and flames.

In conclusion, I loved this Journey to the Canary Islands. As a travel book, it does exactly what Ariana Basciani says: a unique device, neither expensive, nor heavy, that does not require a suitcase or a passport, to take you to discover…the Canary Islands, or any of the places in the travel books that she reviews in Viajar por las ciudades: las otras formas de conocer y conocerse leyendo.

If pressed, I would probably venture that chance was responsible for the recent appearance on my desk of two books, which while from different genres and perspectives, want the same thing: a slow and careful explanation of why this world is so troubled. This may not be the occasion to point out that nothing happens by chance (nihil fit casu in mundo), but nevertheless, that’s exactly what I’m going to do.

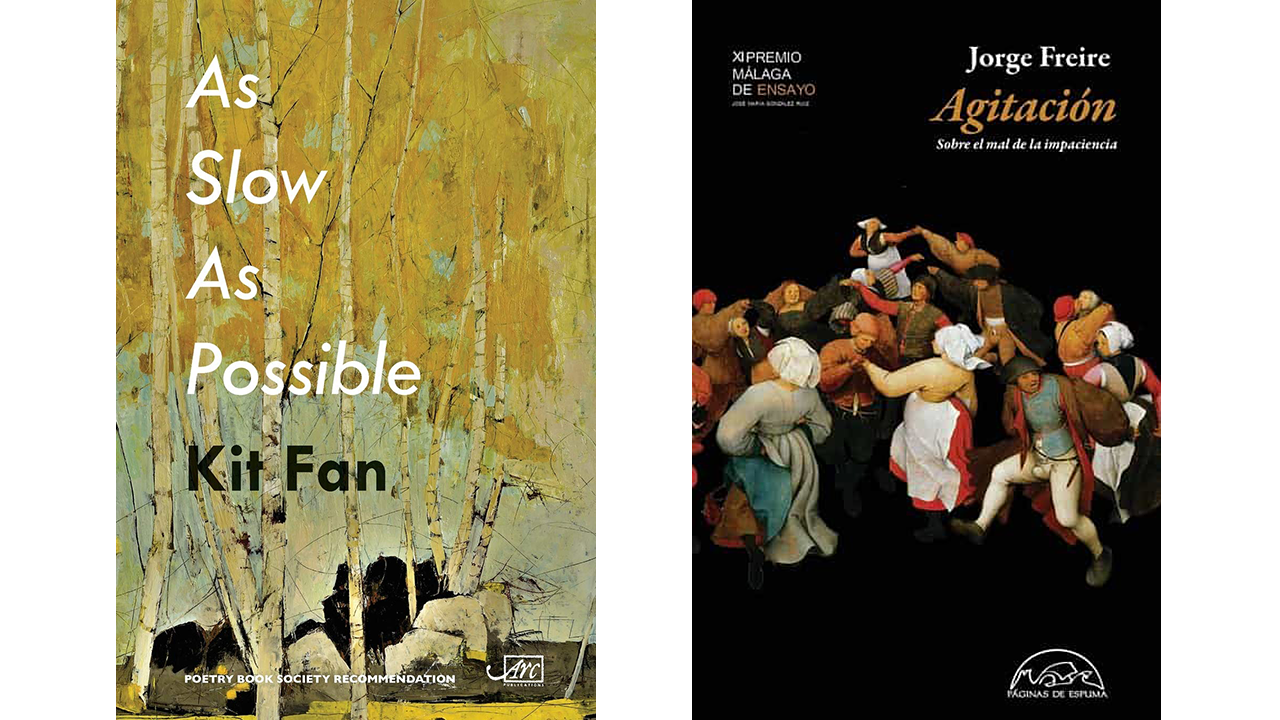

The first is As Slow As Possible, a collection of poems by the award-winning Hong Kong poet Kit Fan. I met Kit Fan online last month, at the IE Foundation’s Prizes in the Humanities, and his way of speaking immediately aroused my curiosity about his work.

The second is an essay entitled Agitación by Jorge Freire. Santander-based lawyer Pilar de la Hera, recommended the award-winning philosopher from Madrid last weekend. By the way, Pilar took part in Spain’s first post-lockdown case by videoconference, as The New York Times’ Raphael Minder writes in Spain’s Courts, Already Strained, Face Crisis as Lockdown Lifts.

When I say that both books want the same thing, I mean that they both want to provide a space for reflection in this runaway world, one in which we not only run incessantly, like hamsters in a wheel, but also forget that There was a time when we were not here, as one of his poems reminds us.

We would do well to remember the words of the Buddhist poet Hanshan, written 1200 years ago: we humans live in blinding dust, like insects in a bowl. All day w go around and around and never get out of the bowl (人生在塵蒙 恰似盆中蟲 終日行繞繞 不離其盆中).

Fan writes from his guts, slowly, driven by the fire in his heart, tempered by the power of his words and intellect. I was captivated by how As Slow As Possible brings together, slowly, steadily, personalities from Eastern and Western culture, ranging from Zurbarán to apocryphal haikus attributed to the enigmatic Chinese painter Fan Kuan (范寬, 960-1030), and on to Brueghel, Banksy, and Sancho Panza (the latter is ironically quoted in the poem Don Kowloon).

In contrast, Freire embarks on a frenetic race of quotes and references, illustrating how the epidemic of agitation, the disease of our era, not only swallows up our entire life thanks to the adrenaline we create (running, being Zen, vegan, rafting in Indonesia…), but also any kind of cultural product at our disposal. When we become agitated we move, but we don’t advance,” he argues. All this agitation seems rooted in our horror of the home. (La grande maladie de l’horreur du domicile diagnosed by Baudelaire).

In short, if, by chance you’ve taken the time to read this text, I can only hope that my words have been sufficient to lure you to explore these two magnificent books slowly and carefully.

In his magnificent Vermeer´s Hat, sinologist Timothy Brook (Chinese name 卜正民) has produced an impressive and unusual piece of research work: has chosen not to focus on the beauty and technical perfection of Vermeer’s paintings, nor his mysterious personal life, nor why one of the greatest painters ever was only recognized two centuries after his death—thanks largely to 19th century French art critic Théophile Thoré. Instead, Brook has produced a meticulous analysis of the objects that appear in five of his paintings, to show us the importance of international trade in the seventeenth century between China and the West, and particularly, Vermeer’s home town of Delft, which played a hitherto largely unknown role until recently.

The first thing Brook does is to challenge the way we look at paintings, telling us to stop seeing them as windows to other times and places. “Chief among these habits is a tendency to regard paintings as windows opening directly onto another time and place. It is a beguiling illusion to think that Vermeer’s paintings are images directly taken from life in XVII century Delft. Paintings are not “taken”, like photographs; they are “made”, carefully and deliberately, and not show an objective reality so much as to present a particular scenario,” argues Brook. Through a careful analysis of these scenarios, Brook creates a map of the world of the time.

With the future of international trade, and particularly with China, a hot topic, Vermeer’s Hat offers a highly stimulating and cosmopolitan perspective of the world.

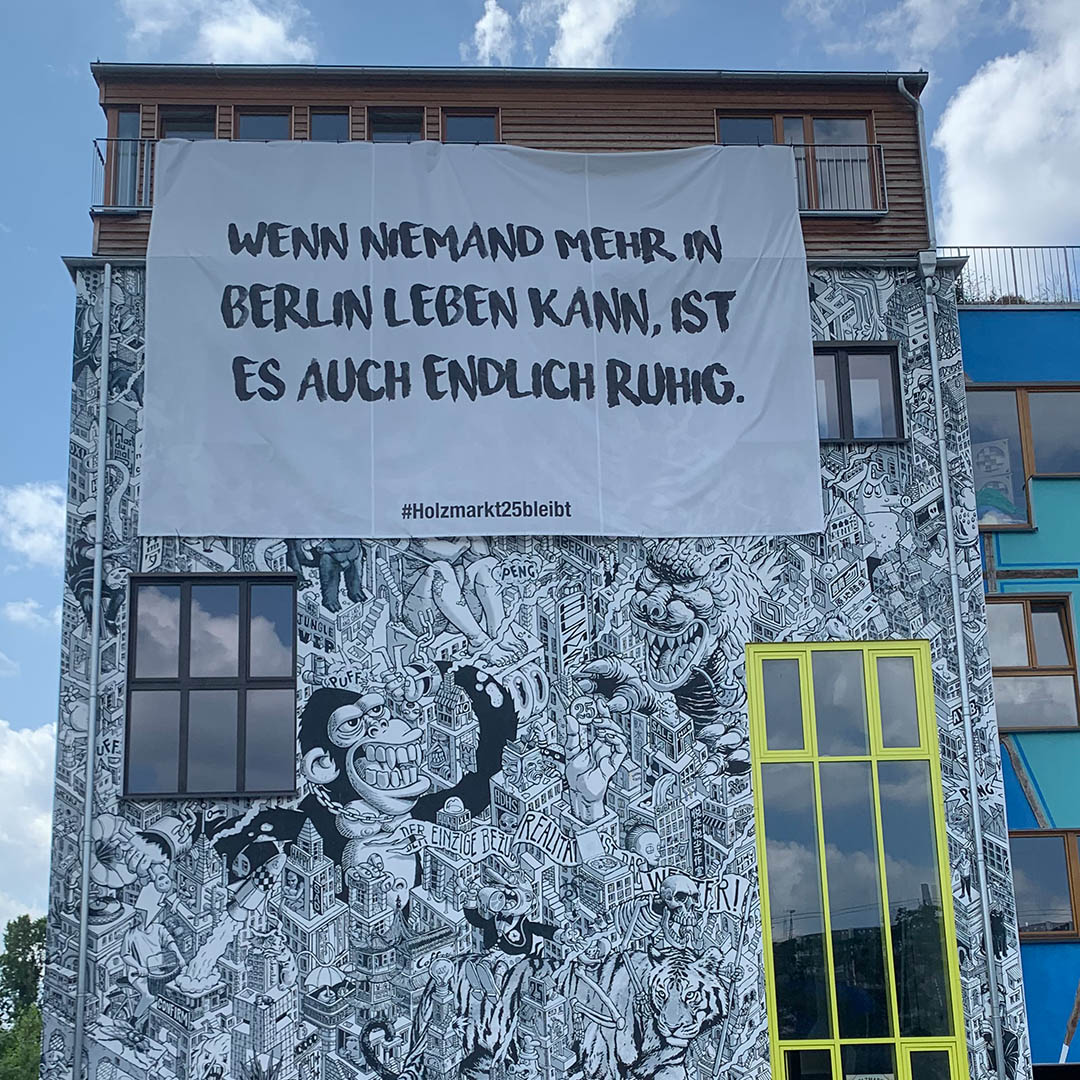

During a visit this weekend to Berlin, I was hoping to continue with my plan (Inhshallah) to write about the Chinatowns I come across during my travels, but there isn’t one in the German capital: the best-laid plans… The closest Berlin comes to a Chinatown is in Kantstrasse, in Charlottenburg, but in reality, Berlin is a graffiti town. Wherever you go, you’ll find a wall or some corner that’s been painted.

I’ve chosen these graffiti from the East Gallery, painted on one of the last remaining stretches of the Berlin Wall along Warschauer Strasse in Kreuzberg, both for their message and their esthetic. If I had to choose one in particular, I’d go for The Persistence of Ignorance, which sadly is the worst photograph, because I’m not such a great photographer, and so part of the graffito is missing. Ignorance manifests itself in so many ways: as lack of knowledge or ability.

As is well known, we come into this world as donkeys, and it is only after a great deal of hard work that education de-donkeys us. It’s a long process, as summed up by the Chinese proverb Live to be old, learn until you are old (活到老, 学到老 huó dào lǎo, xué dào lǎo. Also see The civilizing influence of Lady Gaga).

In short, de-donkeyfication takes a long time; there are few walls as big as the wall of ignorance, although there are many other walls that need to be knocked down, as another of these graffiti points out.

P.S: We would like to thank the authors of the graffii, whose authorship we know: The persistence of ignorance by Karsten Wenzel, Tolerence by Mary Mackey, Pal Gerber

After reading my recent post, Shangri-La, my work colleague at IE Business School, Mar Hurtado de Mendoza, surprised me this week with a question, which I answered with a story I had never told, one filled with happiness and at the same time, sadness.

In 1992, in Zagreb, I met a man who left a lasting impression on me, Juan Carlos Gumucio. A war correspondent, at that moment, he was covering the conflict in Sarajevo for leading Spanish daily El País.

He had come to the Croatian capital to try to forget the miseries of the war and so paid more attention to my former colleague Marta Marín, who remains a friend to this day, speaking with me on a few occasions. On one of those occasions, sitting at a bar, I mentioned my literary concerns. He looked at me, sipped his neat whisky and without saying anything, gestured over the bar that I should get going, or more accurately, that I should get writing.

Time passed and Marta and I finished our glamorous feature on Croatia for Paris-Match, gradually losing contact with Gumucio. Juan González Yuste, war correspondent for El Periódico, told Marta that his old friend had married Marie Colvin, the celebrated Sunday Times correspondent, in 1996 and that the couple had later divorced.

In 2002, having steadily lost contact with them, Marta and I learned from the papers that Gumucio had returned to his native Cochabamba, in Bolivia, having decided, inexplicably for such a dynamic person, to retire. He shot himself that year at the age of 52. Colvin would die a decade later in Homs, an early casualty of the war in Syria, alongside photographer Rémi Ochlik: “murdered while reporting bravely from Syria,” said Britain’s foreign secretary, William Hague, at the time. The film A Private War was based on her incredible life.

González Yuste died in 1999, also aged 52, in a hotel at Barcelona’s El Prat airport while travelling from one war zone to another.

I write this after telling Mar that I have no time for creative writing courses and that if she too has literary concerns, the best thing to do is to get writing, as Gumucio put it. I wrote the story below, What is Strange? in honor of a dreamer who came up against reality.

—

PS: Renée Cortés, a Bolivian colleague at IE University, knows the family of Juan Carlos Gumucio and is familiar with his legend.

What is strange?

Painting by Miguel Panadero

We accept that dream things happen in sleep and that real things happen in reality. It’s strange that we still accept this division between dreams and reality, strange that they aren’t both in the same pile of stuff. Didn’t the poet say that life is a dream where life is reality, and dreams, dreams?

A woman dreams in her own peculiar way about a man pointing to a box that contains a knife who wants to cut down a tree so that it can be used to make something else in the shape of a trapezoid and all this under the presence of the Sun which not for nothing is the King of light. What is strange?

Think as though you were dreaming. Think that before the wind, the whole of the forest was silence. Think that after the wind, it is as though noise suddenly arrived as thought. Think that if you thought like you dream, perhaps you’d dream when you think. What is strange? That reality is a dream?

Moscow, April 23,