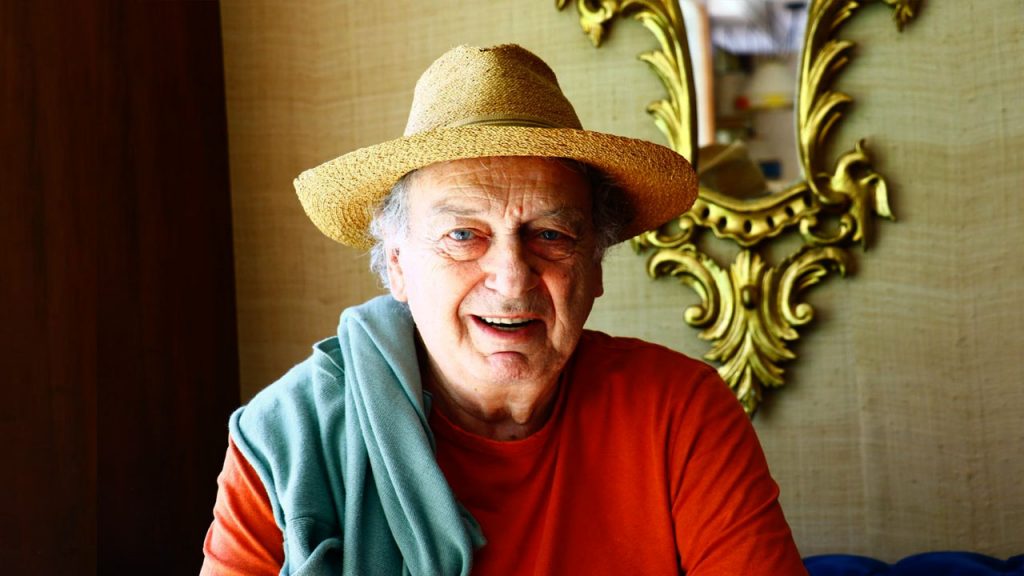

Steven Frears is going to make a film about Billy Wilder, Han-Joon Chang confesses that One Hundred Years of Solitude is his favorite novel, and Carlos Franganillo argues that we tend to idealize the past… All this at the Hay Festival Seville 2024.

Poetry

Steven Frears is going to make a film about Billy Wilder, Han-Joon Chang confesses that One Hundred Years of Solitude is his favorite novel, and Carlos Franganillo argues that we tend to idealize the past… All this at the Hay Festival Seville 2024.

Enrique Gracia Trinidad pays homage to Whitman, Celaya, Lorca, and more.

This new work by Juan Vicente Piqueras, noting that it is his particular cry, or whisper, of anguish and loneliness, as Luis Alberto de Cuenca, president of the jury that awarded Cerezas the II Premio Nacional de Poesía Ciudad de Lucena Lara Cantizani.

Cry of Love (Towards a General Theory of Cavities) offers some concepts about love, poetically trying to bring order to the imbroglios in your heart, regardless of the mess you might have created there.

“Nati, my mother, was born in Tenerife. I once had a sporadic relationship with her, which ended some years ago. We have never been in close contact. She currently lives in another country,”

Pastron#7 says he painted CALLE (street) because in the graffiti world, the talk is always about the “street”, “street art” here, “street artist” there, ad nauseam. So he chose the Spanish word for street, calle, to protest the predominance of English in the arts, as well as in other areas.

At the Hay Festival in Segovia 2020 (Awarded with Premio Princesa de Asturias de Comunicación y Humanidades 2020): Aurora Luque, winner of the XXXII Loewe Poetry Award 2019, The Ambassador of the Neederlands, The Ambassador of Portugal, The Ambassador of Austria and the Portuguese Tourism Office Director recited poetry at El Jardín del Romeral.

The Canarian Garoé tree was believed by some to be sacred, filled with water, it would cry for scorned lovers. Others believe the Teide bird to be the most beautiful of its kind, which nests inside the volcano of the same name, as black as the blackbird, so black that it is blue, while the song says that it is the second star on the right, the path that leads to the island that does not exist (L’isola che non c’è), just as it leads us to see that tree, and that bird, which has only flown in the verses of poets. Everything is magua, melancholy, the feeling of the islands in the magnificent Journey to the Canary Islands, a sentimental portrait of our islands that Juan Cruz wrote at the suggestion of the late Peter Mayer.

Today, a travel book seems anachronistic, almost dystopian. But a book of travels, or of something else, is the story of a horizon, of a hope, and tells of a way of seeing things. And as we travel through life, the question is always how we continue that journey, for which the story of other lives and other journeys, helps. I understand then that we must seek hope to continue living, says Cruz, citing the Canarian poet José Luis Pernas.

I would never have imagined myself reading a book like this in late July. However, it seduced me, just like the Rafael Alberti bookstore in Madrid, where I went for my weekly hit of dopamine from Lola Larumbe. But instead, I ran into Juan Cruz, who had just arrived to sign books. An encounter between Canarians in the land of the Goths, far from the fish tank of the archipelago, aroused the camaraderie that all encounters do between outsiders who are far from home.

I told him that during lockdown I had met Lola Larumbe by chance one Saturday, out looking for tobacco, and seeing movement from within the closed bookstore, I knocked on the door, only to be politely told the shop was closed to customers. But when I told her that I simply wanted a book of poetry, whichever she thought best, she selected one, and since then I have gone back, to be there again, like the poem Volver from Eloy Sánchez Rosillo’s Confidencias, the book she initially chose.

-Well, I can recommend this book – from the only poet who made Vargas Llosa cry, offered Juan Cruz.

-No, thanks,” I said, ignoring the book he was showing me. I want something recommended by that lady over there. Lola Larumbe, whose name I still didn’t know at the time, had just appeared at the back of the bookstore. And amid the laughter, she asked me mine.

That day, from the many books that Cruz was due to sign, I chose Journey to the Canary Islands, over the course of which, he explores what the islands are, and what they have been and inspired by. The reader is grateful he avoids the affectation of so many, if not all, of referring to Gabriel García Márquez as Gabo. That said, in balance, what’s missing among so many fine literary allusions are some quotes by women, such as Cruz’s prodigious fellow Canarian Mercedes Pinto Armas de la Rosa y Clós, whose novel, El (Him), was made into a film of the same name by Luis Buñuel in 1953. Thirty years earlier, during the dictatorship of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, she gave a lecture in Madrid entitled Divorce as a hygienic measure. She went into exile, as did Miguel de Unamuno, whom Cruz, along with Aldecoa, Humboldt, Breton, and so many others, does cite at every opportunity.

Pablo Neruda, who was deeply impressed by her, wrote the words below during her lifetime, and which were put on her tombstone after she died in 1976.

Mercedes Pinto lives in the wind of the storm.

With her heart facing the air.

Energetically alone. Urgently alive.

Sure of successes and invocations.

Fearful and kind in her tragic garment of light and flames.

In conclusion, I loved this Journey to the Canary Islands. As a travel book, it does exactly what Ariana Basciani says: a unique device, neither expensive, nor heavy, that does not require a suitcase or a passport, to take you to discover…the Canary Islands, or any of the places in the travel books that she reviews in Viajar por las ciudades: las otras formas de conocer y conocerse leyendo.

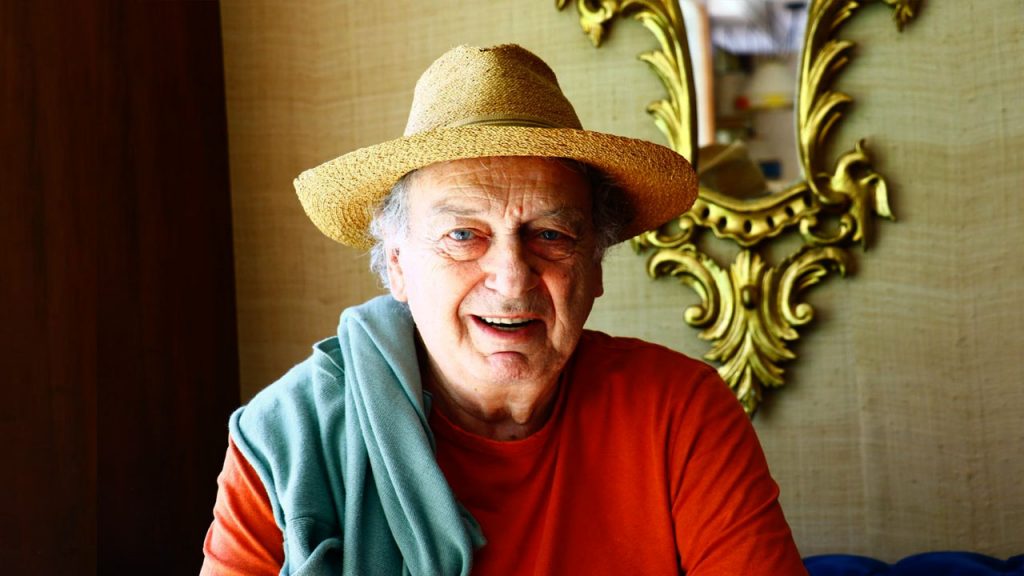

If pressed, I would probably venture that chance was responsible for the recent appearance on my desk of two books, which while from different genres and perspectives, want the same thing: a slow and careful explanation of why this world is so troubled. This may not be the occasion to point out that nothing happens by chance (nihil fit casu in mundo), but nevertheless, that’s exactly what I’m going to do.

The first is As Slow As Possible, a collection of poems by the award-winning Hong Kong poet Kit Fan. I met Kit Fan online last month, at the IE Foundation’s Prizes in the Humanities, and his way of speaking immediately aroused my curiosity about his work.

The second is an essay entitled Agitación by Jorge Freire. Santander-based lawyer Pilar de la Hera, recommended the award-winning philosopher from Madrid last weekend. By the way, Pilar took part in Spain’s first post-lockdown case by videoconference, as The New York Times’ Raphael Minder writes in Spain’s Courts, Already Strained, Face Crisis as Lockdown Lifts.

When I say that both books want the same thing, I mean that they both want to provide a space for reflection in this runaway world, one in which we not only run incessantly, like hamsters in a wheel, but also forget that There was a time when we were not here, as one of his poems reminds us.

We would do well to remember the words of the Buddhist poet Hanshan, written 1200 years ago: we humans live in blinding dust, like insects in a bowl. All day w go around and around and never get out of the bowl (人生在塵蒙 恰似盆中蟲 終日行繞繞 不離其盆中).

Fan writes from his guts, slowly, driven by the fire in his heart, tempered by the power of his words and intellect. I was captivated by how As Slow As Possible brings together, slowly, steadily, personalities from Eastern and Western culture, ranging from Zurbarán to apocryphal haikus attributed to the enigmatic Chinese painter Fan Kuan (范寬, 960-1030), and on to Brueghel, Banksy, and Sancho Panza (the latter is ironically quoted in the poem Don Kowloon).

In contrast, Freire embarks on a frenetic race of quotes and references, illustrating how the epidemic of agitation, the disease of our era, not only swallows up our entire life thanks to the adrenaline we create (running, being Zen, vegan, rafting in Indonesia…), but also any kind of cultural product at our disposal. When we become agitated we move, but we don’t advance,” he argues. All this agitation seems rooted in our horror of the home. (La grande maladie de l’horreur du domicile diagnosed by Baudelaire).

In short, if, by chance you’ve taken the time to read this text, I can only hope that my words have been sufficient to lure you to explore these two magnificent books slowly and carefully.

I don’t remember exactly when I wrote La distancia. It must have been between March and June 2019. Back then, not even the wise men had any idea what was coming. As Constantine Cavafy wrote (Σοφοι δε προσιόντων), the mystical clamor of approaching events was never heard.

I can’t help feeling that everything has taken on another meaning and that distances have grown longer.

Illustrations by Miguel Panadero – The Distance