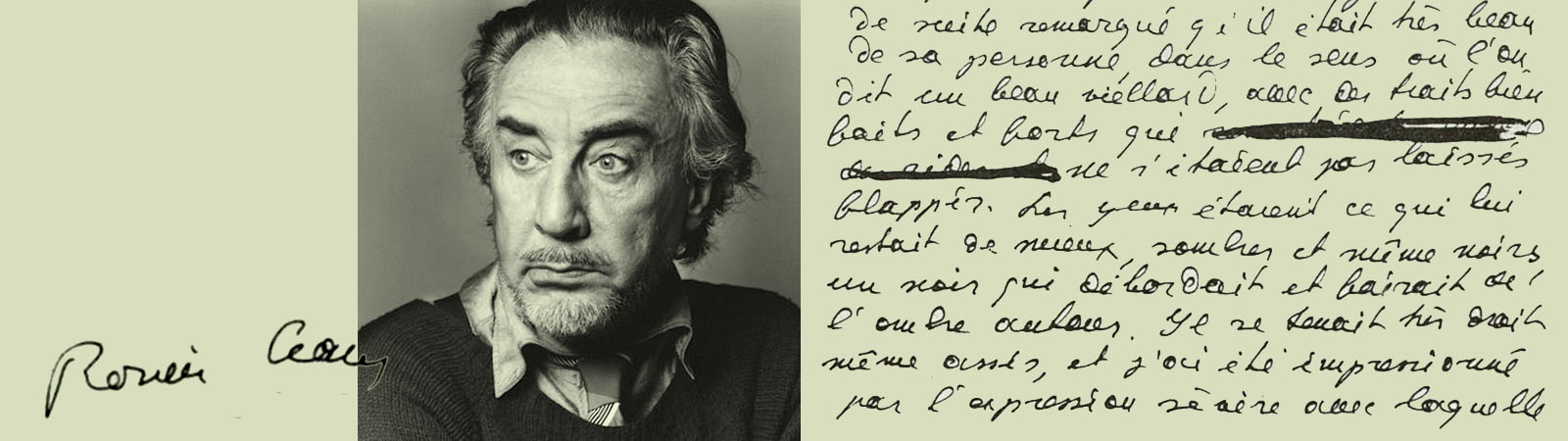

Few writers can claim to have led a life as intense as Romain Gary’s. Few writers can claim to have written under so many pseudonyms. A few writers can claim to have loved as much as he did. But no other writer can claim to have won the Goncourt Prize twice.

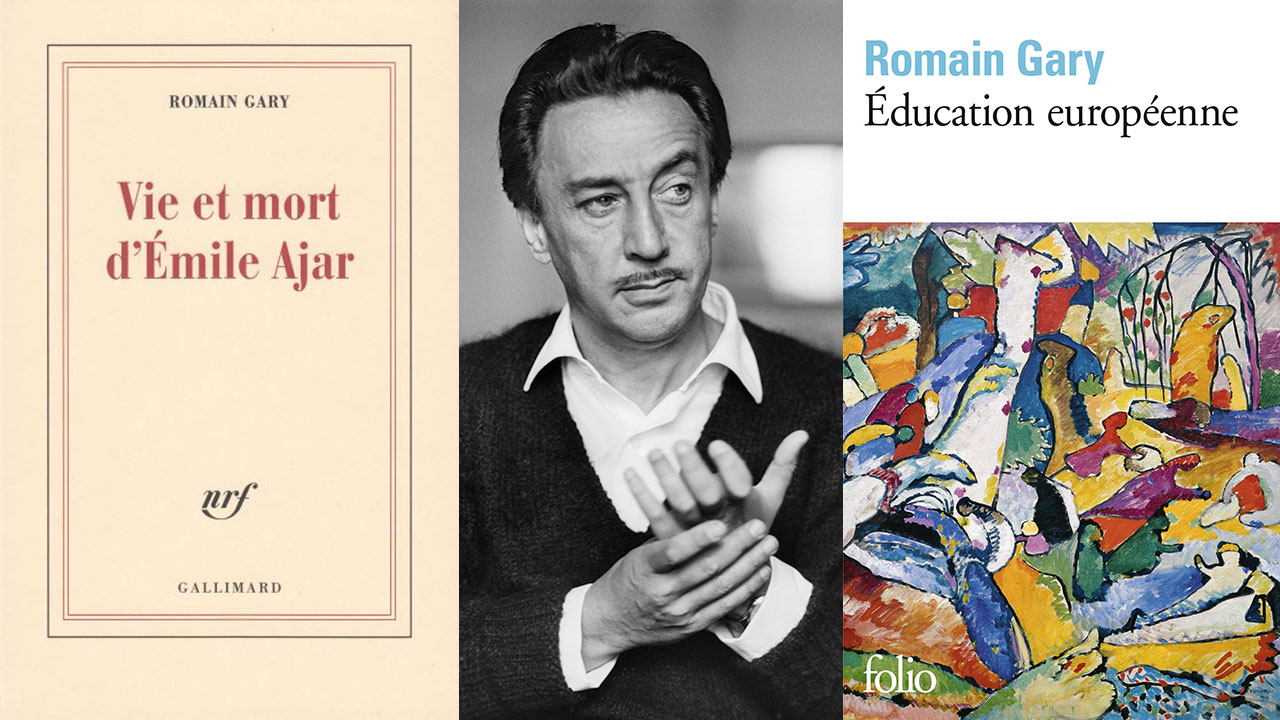

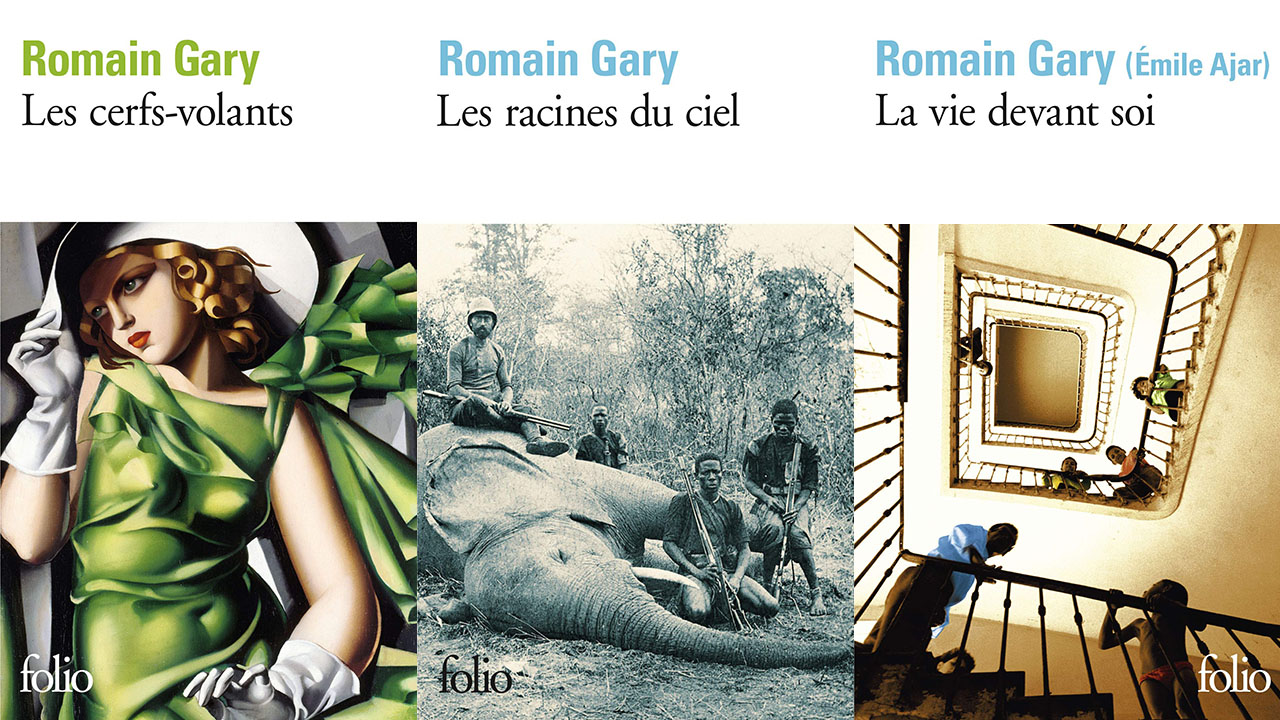

I’ve just finished reading The Life and Death of Émile Ajar, by and about one of my favorite writers, or should I say two of my favorite writers: Émile Ajar was one of Gary’s many aliases, which is how he managed to break the Goncourt Prize rule that it can’t be awarded to the same writer twice, after winning it first in 1956 with Roots of Heaven, and then again as Émile Ajar with Life Before Him in 1975.

Born in 1914, by his sixties, and with a distinguished literary career behind him, Romain Gary simply got tired of being himself, unhappy with the image the public and the intelligentsia had bestowed on him, and more specifically by the all-seeing, all-knowing Jean-Paul Sartre’s comment that it would take 30 years to find out whether Gary’s 1945 A European Education was the best novel about La Résistance or not. Gary was not about to accept that he was finished.

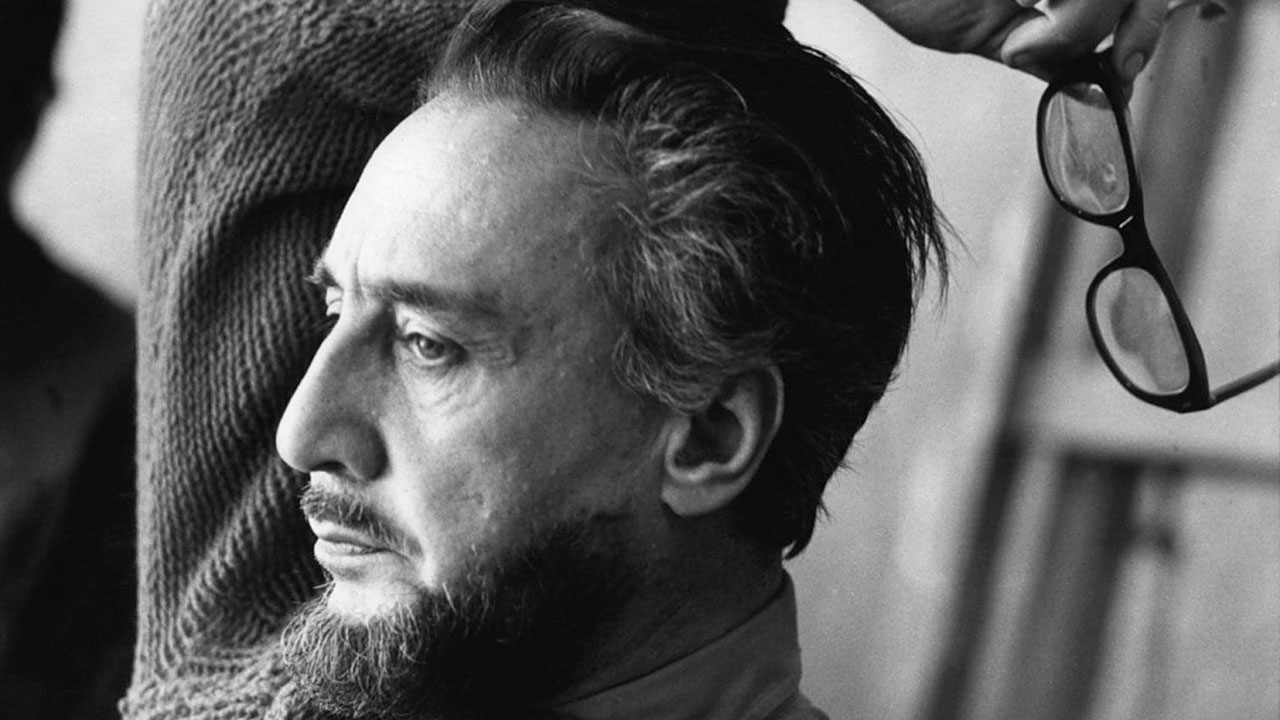

He was fed up with people describing his various lives as an aviator, diplomat, writer, polyglot, as symbols of a full life, when he simply saw himself as an adventurer, driven by an irresistible lust for life. “The truth is that I was deeply touched by man’s oldest temptation: the multiplicity of Prometheus,” he wrote in The Life and Death of Émile Ajar.

So he reinvented himself again, convincing a friend to send the manuscripts of a certain Émile Ajar to the Gallimard publishing house. He wrote four novels under this pseudonym, and one of them won him the Goncourt again, the jury unaware of Ajar’s true identity. Other nom de plumes included Fosco Sinibaldi and Shatan Bogat, along with his real name, Roman Kascew.

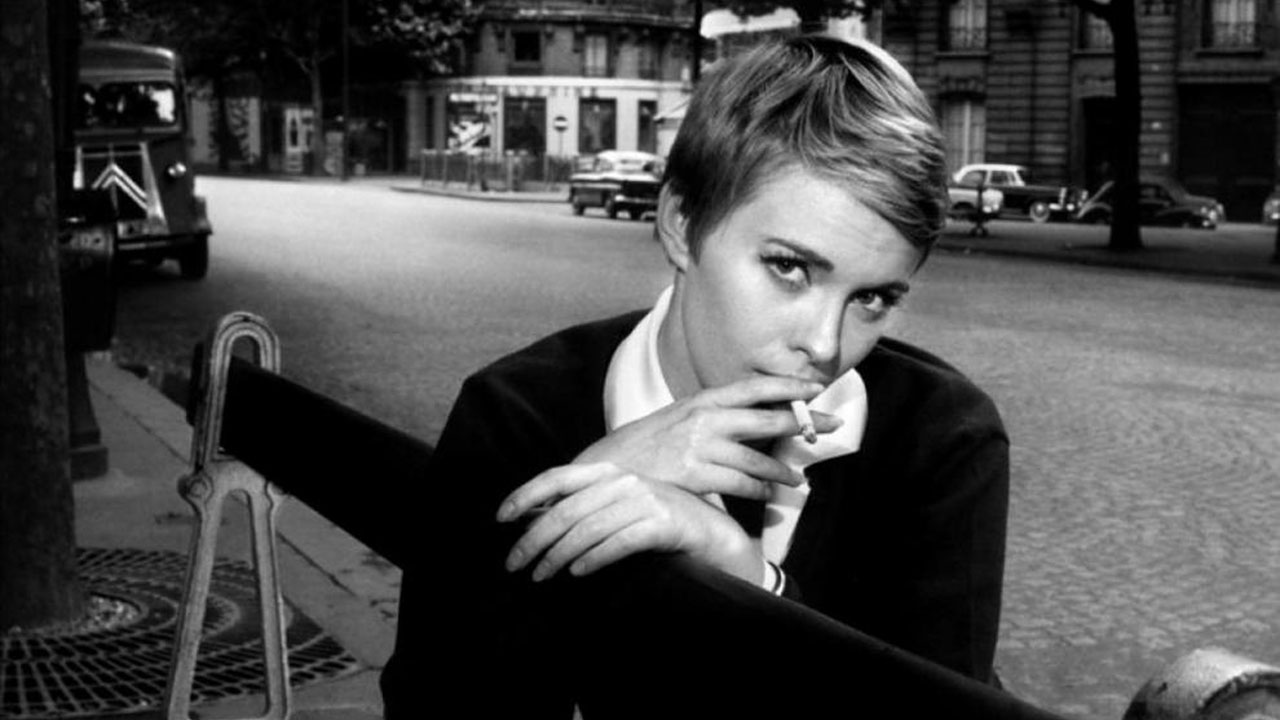

There’s no point in discussing Sartre’s opinion of A European Education, but there is no denying that Gary’s The Kites is not only one of the best books about the Second World War, it is also an unforgettably bitter-sweet love story, perhaps drawing on his time married to Jean Seberg, mother of his only son.

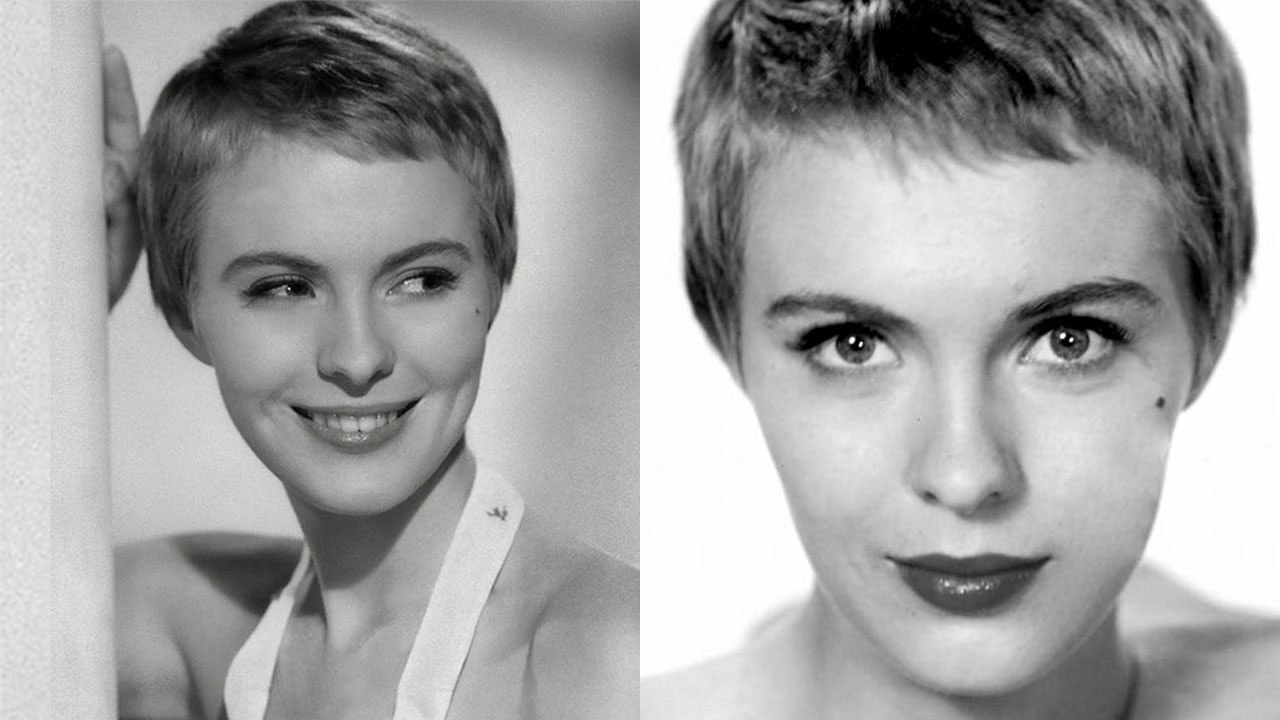

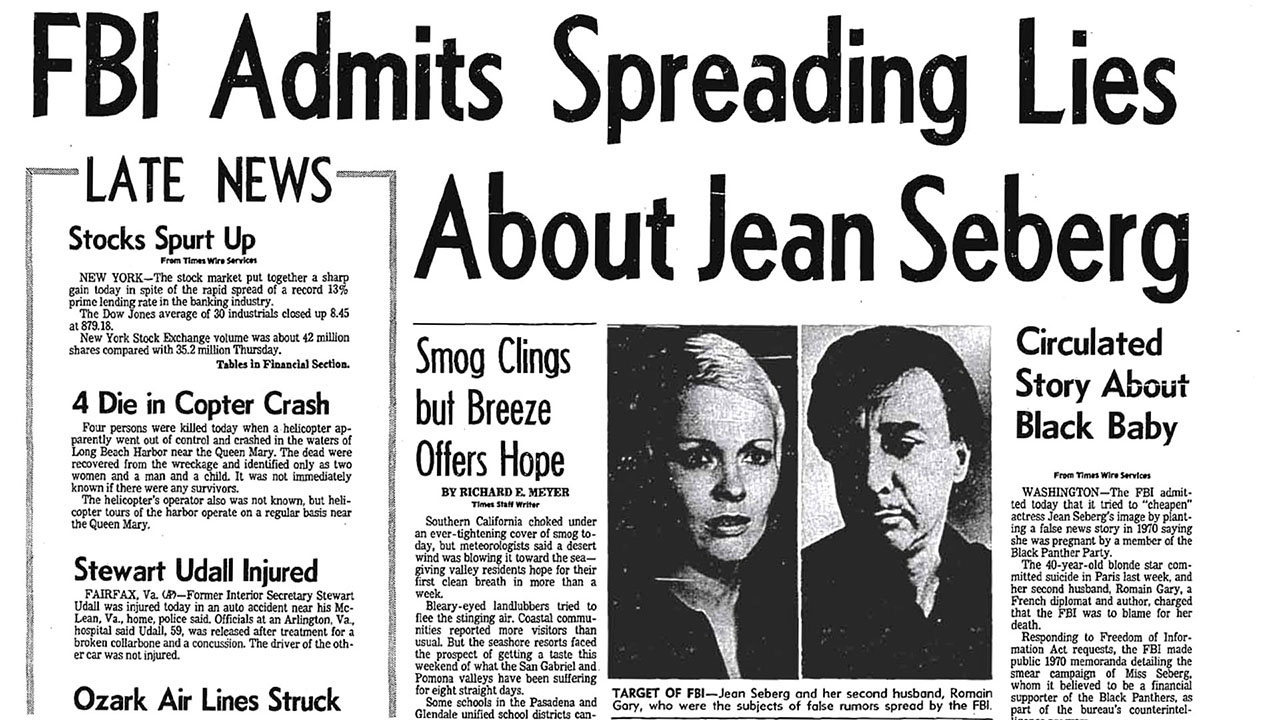

Both lives ended tragically. Seberg committed suicide in 1979 at the age of 41. She was found dead in Paris in her car with a note in her hand, addressed to her only son, Diego: “Dear Diego: I can’t stand the pressure anymore. Forgive me. Be strong.” Her support for the Black Panther movement had angered the FBI, which for more than a decade had put all its efforts into making her life impossible.

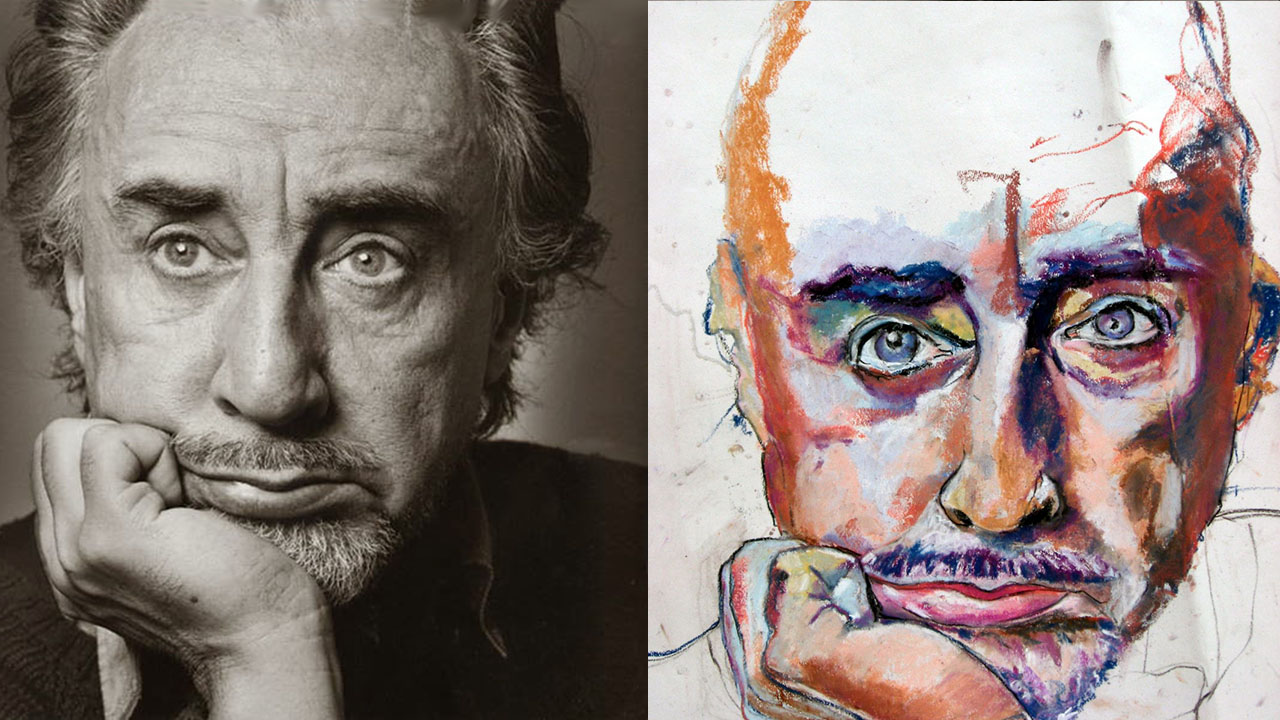

A few months later, at the age of 66, Romain Gary blew his brains out with a Smith & Wesson. “Anybody who has created himself has the right to destroy himself,” wrote Nuria Barrios in 2008. With Gary died a host of other writers: Roman Kacew, Shatan Bogat, Fosco Sinibaldi, and of course Émile Ajar. “What no one knows is which of them pulled the trigger,” concludes Barrios, who has just published Todo arde, a powerful reworking of the myth of Orpheus set in Madrid’s drug underworld.

I have to say, having read the works of most of Gary’s alter egos, I still don’t know which is my favorite.