French street artist Combo has become a symbol of diversity, celebrating co-existence and encouraging us to “Fear no one, fear nothing”. He has plastered Hong Kong with Google advertisements banned in China and been beaten up while at work in Paris, but undeterred, he continues to spread his message.

We can’t avoid acting in accordance with plans, after all, a plan provides security and reduces our degree of uncertainty to tolerable levels. That said, it’s also nice to forget the plan and allow life to surprise us, because a surprise can often give us that vital hit we were hoping for or simply lift us out of our planned boredom.

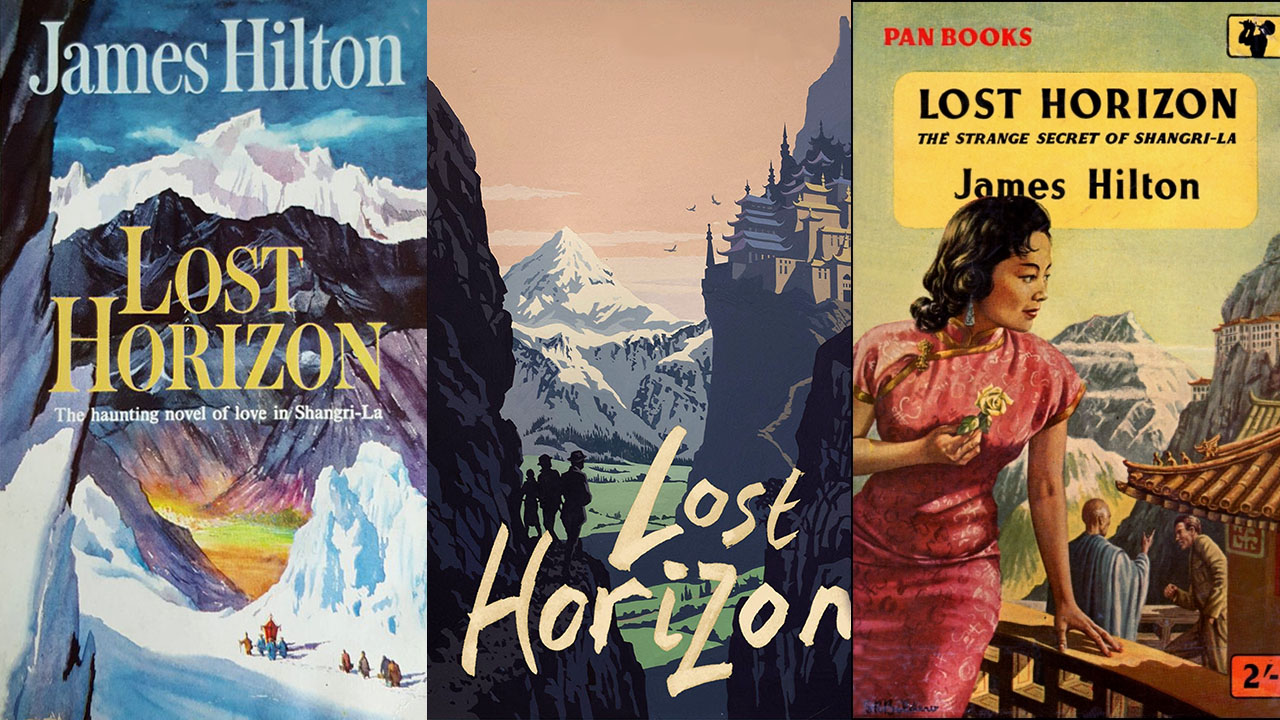

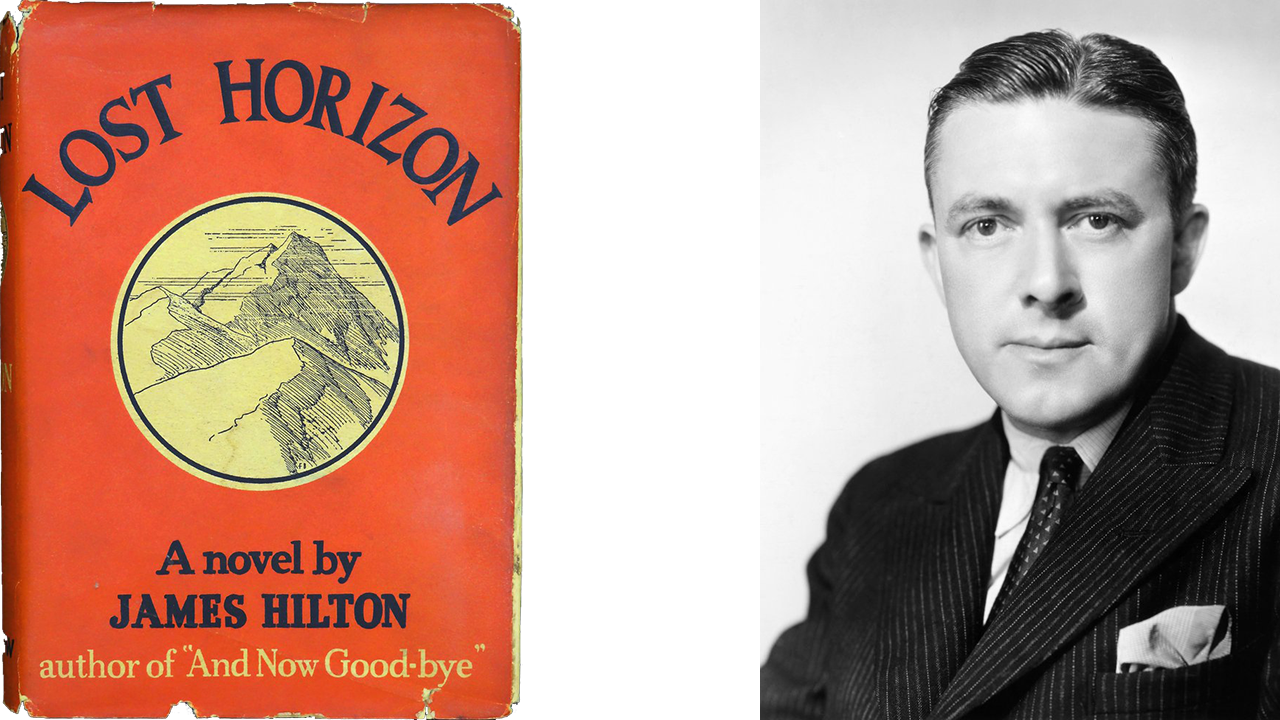

I say this because flying between Beijing and Shanghai last week, I picked up a copy of the China Daily and half-heartedly began to scan its pages. When I opened it, I came across a great article called Where is Shangri-La? by Simon Chapman and DJ Clark about one of my favorite books, Lost Horizon, by the writer and prolific smoker James Hilton, who was born in 1900 and died at the early age of 54.

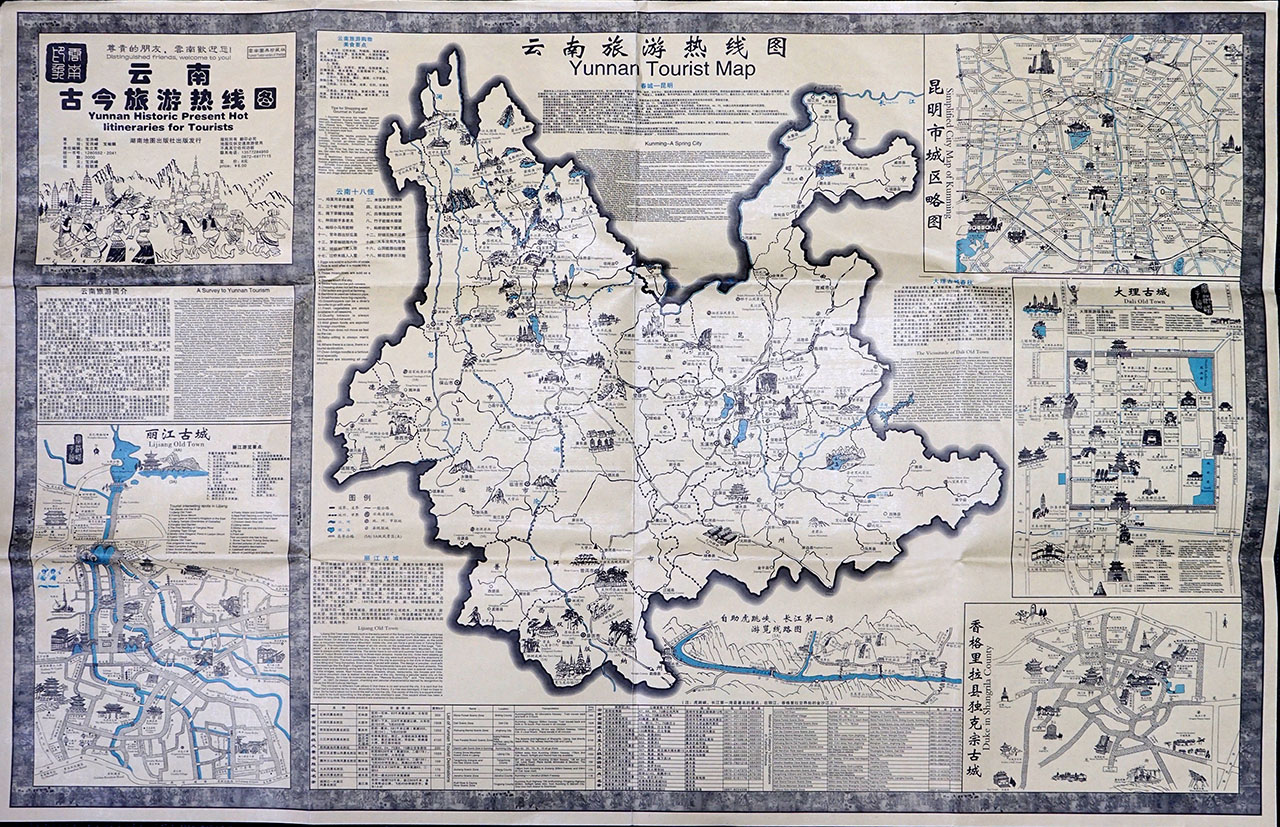

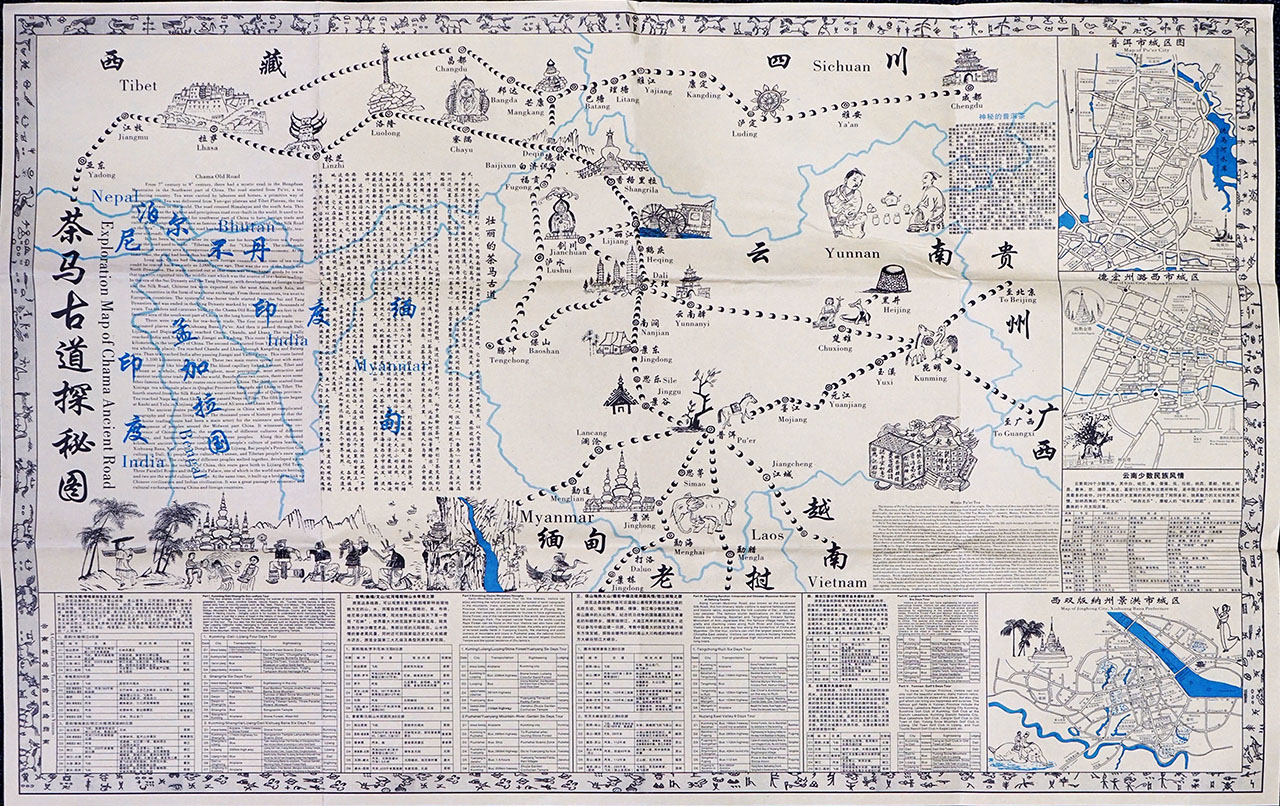

Needless to say, Lost Horizon, published in 1933 and an immediate international best-seller, is the origin of the term Shangri-La, a fictional Tibetan utopia that has not only captured the western imagination, along with other mythical places such as El Dorado and Xanadu, but also lends its name to an international hotel chain. Any number of communities have claimed to be the origin of the paradise Hilton invented (incidentally, he never visited the region), among them, Lijiang, Zhongdian, both in China’s Yunnan province. Shangri-La in Chinese is written 香格里拉 (Xianggelila).

Chapman and Clark focus on the question of why Hilton never admitted that the earthly paradise in his book was based on a series of articles written by the Austrian Joseph Rock published in the National Geographic, while accepting the lesser influence of Father Évariste Régis Huc.

I’ll leave you with the beginning of the novel, as said, one of my favorites, which is nothing more nor less than a great story well told: “Cigars had burned low, and we were beginning to sample the disillusionment that usually afflicts old school friends who have met again as men and found themselves with less in common than they had believed they had…

Shortly before a menino da rua snatched my cellphone in downtown Sao Paulo’s Praça Joao Mendes on Sunday, April 28, I had written a few brief notes about my future plans: in the city’s Chinatown and The New Silk Roads (see below).

I find what happened to me later strange. If there’s one thing we’re all worried about, it’s the future, but the future is nothing more than a hope. We hope to finish a post, earn more money or we hope that the world will become less crazy. As we know from experience, there’s no way that things are going to change in the immediate future, so we inject ourselves with the anesthesia of hope. The thing is that in our minds, as in fiction, things make sense. But reality is something else and makes no sense or has so many senses that they escape us. For me, a reality check robbed me of the immediate plans in my head and made me think once more about how fleeting everything around us is. I’m not about to get all transcendental, but this is a good moment to remember Tomara (Inshallah) by the great Vinicius de Moraes, because we never know when the end of the future we store in our small brains will be:

E a coisa mais divina

Que há no mundo

É viver cada segundo

Como nunca mais

It’s the most divine thing

There is in the world

To live each second

As though it were the last

“I’m in Brazil, in the country of the future, as Stefan Zweig called it in one of his last books. The idea is to take advantage of my blog, On China & other niceties, to write a series of posts about the Chinatowns around the world I visit as part of my work. Sao Paulo’s Chinatown is very unusual, if only because it was founded by Japanese immigrants, and today it is also home to Chinese and Koreans and its name no longer relates to its Japanese founders. Perhaps this is what I find so interesting, because I’ve just finished reading Peter Frankopan’s 2015 book The New Silk Roads, in which the British historian provides an excellent outline not just of the growing importance of China and its rivalry with the United States, but also because of what the Far East means to the world today, as he notes: However traumatic or comical political life appears to be in the age of Brexit, European politics or Trump, it is the countries of the Silk Roads that really matter in the twenty-first century.”

Zhou Dunyi & the lotus flower

The other day I showed my colleague Jaime Pascual, who claims to dislike poetry, a bad poem of mine (see below), called Distance, which vaguely (distantly) echoes the comments of eleventh century Chinese philosopher Zhou Dunyi (周敦頤) about Tao Yuanming’s (陶渊明) love of lotus flowers, writing seven hundred years earlier: “The lotus flower can be only appreciated from a distance, touching one is blasphemy” (可远观而不可亵玩焉)…The lotus flower emerges from the mud unsoiled (出淤泥而不染).

Perhaps we too should learn to keep our distance as we go about our daily lives, the better to remain unsoiled, like lotus flowers, oblivious to the mud around us. Jaime said he liked the idea of my poem and I was glad he had grasped it through poetry. I am convinced that poetry alone can express things in such a way as to make us believe there is still a chance of emerging from the mud unsoiled!

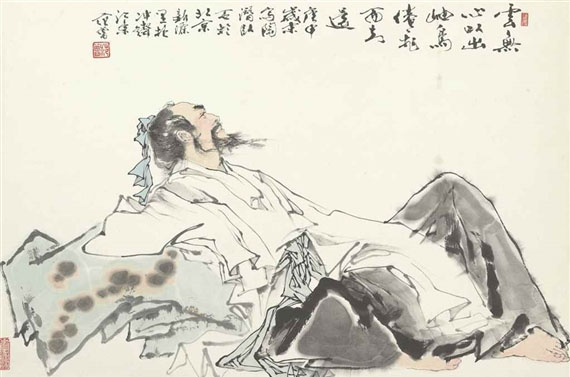

The Poet Tao Yuanming (陶渊明)

DISTANCE (1)

You wander through space.

Distance annoys. Distance intrigues.

You leave one place to get to another.

And when you get there…

It’s clear you don’t like what you find.

It could have been different.

In any event, where there’s distance you want to reduce distance.

Distance is stronger than taste.

You only want to conquer distance.

That’s why you travel from origin to destination.

Distance annoys, distance intrigues.

You only want to conquer distance.

(1).

This poem was not included in my book Dibugrafías

Life is life and not the thing we want it to be. That’s why it so often slips out of our hands and why the story of every life boils down to the story of the tension between the urge to do the thing you want and the combination of circumstances bent on keeping you from it, let’s say, your dream. It seems unnecessary to stress that this tension creates a lot of frustration. Put like this, life tends to look more like a process of breaking down – as Fitzgerald wrote – than anything else, like some kind of title bout, where all that matters is staying on one’s feet as one’s ride the punches. The progress of an education, whether a contender’s, for the Heavyweight Championship of the World or one’s own, has always interested me (that´s why I like the Chinese proverb, 活到老, 学到老 huó dào lǎo, xué dào lǎo, which means something like: [If one] lives to an old age, [one will continue to] learn until old age.)

Long ago, perhaps aware of the punches coming my way, I came up with a very small stratagem – sometimes, small things are crucial – to help me escape from the frustration, bad moods, or weakness, that life can deliver. The stratagem is simply a list of 10 delicious dishes I could choose from to give me back my lust for life or that energy I lacked after the latest blow. I have yet to complete the list. Moreover, a lady once said to me: “Let me tell you your favourite dish”. She didn’t say much more, because it seems that at some point in her life she had acquired the habit of not doing so, of politeness, and converted said habit into a question of manners, like when one leaves a tiny bit of food on the plate to show one’s host that the meal was abundant. Oh les femmes!

Please find below my list, in no particular order, because each has its moment.

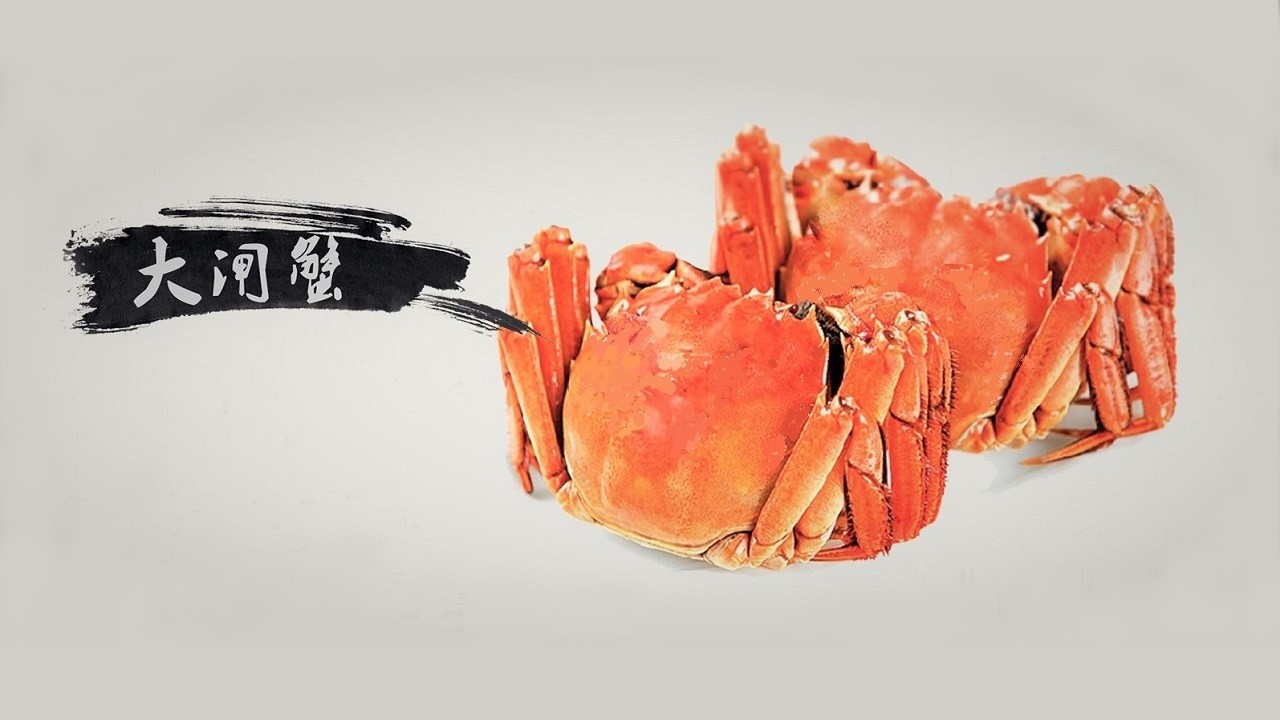

– Dazhaxie (大闸蟹), wonderful Shanghainese river crabs, only available from late September to November (see photo).

– Chayedan (茶葉蛋) or Tea egg: delicious eggs cooked in spices, soy sauce and black tea leaves.

– Toro (とろhiragana or トロ katana), the fatty cut of tuna belly.

– Caviar, which needs no explanation.

– Morcilla, or spicy black pudding, from Leon, in northern Spain.

– Escamoles, a Mexican dish made from ant larvae and pupae.

– Spanish dry cured ham (jamón ibérico).

– A juice of Acaí, made from a Brazilian berry.

As you can see, the list is incomplete and needn’t stop at 10, which when all is said and done, is simply a number we’ve chosen from our habit of rounding up things, a sort of security blanket to ward off our loneliness and frustration. By the way, another femme, French of course , said you do not forget Le Champagne!!!

As you know, the Chinese Zodiac, also known as Sheng Xiao (生肖), is based on a twelve-year cycle. Each year in that cycle is related to an animal sign. These signs are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog and finally, the pig. AIl is calculated according to the Chinese lunar calendar. Since this coming year is the year of the pig, we all have to find out what is the relationship of our own animal sign, the snake in my case, with the pig, in order to figure out how our life is gonna be this year. It seems the beneficial pig effect on the serpent will be reflected in my revenues and some good luck in any new ventures I might undertake. Will I strike it lucky? Let’s have a closer look.

I suppose living a life can be compared to writing a novel. In theory, we have a whole life ahead of us: a pile of blank pages we can fill with words. People who write novels or who live supposedly successful lives always say how easy it is: it’s just a question of getting down to it. They give the impression they’re always headed in the right direction and that everything they do has, or had, a goal or a purpose to it. Does the pig, or any of the other Chinese Zodiac animals, give a hand to them?

In contrast, I have to confess that I have a terrible sense of direction, and whenever I go somewhere, be it on foot, by motorbike, or by plane, I always think I am headed north, i.e. in the right direction, even though I might be going south. I really have tried to get my head round this, but with little success. I was born in Brussels to a mother from the Canary Islands and an Ecuadorian father, so I did wonder if my family’s ‘Southern Roots’ had disorientated me to the extent that I didn’t even know where the centre was any more. That’s the way things are; I’m not going to go into why I prefer the north because of my complex about the south, or because it’s more developed, or whatever… I doubt the pig can give me any directions!

If each place is its own centre, the same goes for each life, and the same goes for maps; their centre is relative: it depends on the country where you buy them. If you are in China, the centre of the map branches out from there, and if you are in Mali, the same principle more or less applies. In point of fact, when we examine our lives and place in the great scheme of things ours is the perspective of a mosquito. When we talk about life, and not some auto-life, what do we really mean?

Let’s dig a little deeper. I picture a huge GoogleBio focusing on different lives. Like the countries listed on Google Earth, when our lives are seen from the perspective of a roll call, they all look the same; any differences are simply details. These details may be important for those concerned, but they are so trivial, so tiny; barely changing our mosquito’s perspective, that without wanting to, we come up against the limits of existence; with that unbearable lightness of being.

I’m saying this because there is something unreal about this vivre à l’essai, this putting our lives to the test all the time: we can do something, or do the complete opposite without it affecting our existence one iota. ‘Can’t we do anything right (1)?’ , Goethe once asked. Well, I’m afraid we can’t. We don’t do anything right, and worse still, we have very little room for manoeuvre. What ill luck we have, my dear pig!!!

Some Details

It might seem trivial, but the day I was given my Chinese name was a momentous occasion. Not so much for the event itself, when I didn’t really take it in, but for the significance it took on later. Things still existed, even before they had a name, but they were somehow different; I would say their existence was diminished. So, when they called me Táng Mènglóng (唐梦龙), I somehow felt that I had acquired a complete existence again, perhaps because this baptism created another way of existing in the world, and possibly reflected how I had changed over the years. Maybe it wasn’t even that: perhaps it merely confirmed what I had always been. It’s at this point where I begin to have doubts, and, going back to the subject in question, I’m never sure about the extent to which our decisions make any differences to our lives. Probably none.

Due to the peculiarity of Chinese writing, and also the fact that the language is replete with homophonic words, the characters chosen for names are vitally important. A good example is the word 梦 (meng: to dream) which can be spelt (meng): meaning ‘the first month in a season’. It also means ‘older brother’, but more importantly, it is also the first character of the name of the 4th-3rd century BCE Confusian philosopher Mencius (孟子 Mengzi) . The fact my teacher chose a character which refers to a dream world imbues my name with an oneiric, idealistic nuance, which it wouldn’t have otherwise.

Moreover, this character 唐 (Táng), which would be my new surname, also connotes the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), considered the most glorious period of Chinese rule. The third carácter 龙 (Lóng) means ‘dragon’, which is one of the symbols of China. This, coupled with the fact that these three characters in Chinese phonetics sound good together, means that when I say my name I am often complimented, given that I am the dragon which dreams of the Tang dynasty. At the same time, the name also conjures up the Ming dynasty writer Feng Menglong (冯梦龙), who lived between 1574 and 1645.

That said, an ice cream called Menglong (梦龙) has become popular in China, as a result of which people are increasingly likely to say “Ah, like the ice cream!” when I tell them my name. I can’t do anything about it. If you look at the photo, you can see the problem.

Spanish friends say my Chinese name Menglong sounds like the word “melón“, and I suppose at the end of the day, that’s what it boils down to. “A bit like a melon” means a “bit nutty” in Spanish, and that’s not far from the truth. Needless to say, that wasn’t how I imagined things would turn out. C’est la vie. Dear pig, can you still give me a hand?

(1) “Sage, tun wir nicht recht?” is Goethe’s original quote.

Back in October 2018 I met FT´s management editor Andrew Hill at Financial Times premises. He then talked enthusiastically about the release of his new book in 2019. Well, the time has come and his book Ruskinland: How John Ruskin shapes our world is now available for pre-order. I have to say that his enthusiasm about the book sparked my interest on John Ruskin. Needless to say, the following day I bought a copy of Ruskin´s Unto this Last. Here some thoughts, while I wait to receive my copy of Ruskinland…

When the idea of writing a post on Unto This Last occurred to me, I instantly thought of G.K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill, and in particular his humorous chapter, Introductory Remarks on the Art of Prophecy. Whatever else he might have been Ruskin was a species of prophet, as Andrew Hill says in his enlightening introduction:

“Given the failure of almost everyone to foresee the financial disaster of the late 2000s, Unto This Last now merits re-examination. The latest crisis shattered the confidence of market economists –the same smugness Ruskin was attacking in 1860–and fueled many specific concerns that he would have recognized and shared: worries about excessive pay and bonuses, about the use and abuse of wealth, and about the purpose of work.”

I must admit that if only by force of circumstances Unto This Last has now earned the status of a historical essay dealing with the past. But the book is not so much an attempt to render an image of the economic state of Britain in the 1860s, as a study of the foundations of political economy itself: as a result, I would venture to say that the book is highly relevant to the situation we face today, particularly the five things a Ruskin CEO should do, among them, robust leadership, rather than those heart-warming statements issued by contemporary business leaders, such as: “every person has leadership responsibilities and potential.”

As Andrew Hill comments, Ruskin would probably have found this cheesy motivational approach feeble. This kind of language is what Chinese netizens mockingly call “chicken soup” (鸡汤jītāng ), a catch-all term for gooey, feel-good essays that might belong in a Chicken Soup for the Soul type book, along the lines of “Ten things Jack Ma taught me.”

Returning to Chesterton: “The human race, to which so many of my readers belong, has been playing at children’s games from the beginning, and will probably do it till the end, which is a nuisance for the few people who grow up. And one of the games to which it is most attached is called, “Keep tomorrow dark”, and which is also named “Cheat the prophet”. The players listen very carefully and respectfully to all that the clever men have to say about what is to happen in the next generation. The players then wait until all the clever men are dead, and bury them nicely.”

It would seem Ruskin is refusing to lie still in his grave: he admitted that the essays of his book “were reprobated in a violent manner… by most of the readers they met with” when they were first published in Cornhill Magazine, but then noted sarcastically, à la Chesterton, when they were published in book form: “So I republish the essays as they appeared. One word only is changed, correcting the estimate of a weight; and no word is added” !!! (The bold letters & the exclamation marks are mine!!).

In conclusion, all I can add is that Unto This Last is a very good read and is overdue for rehabilitation, as Andrew Hill argues.

P.S.: Unto this Last had such an impact on Ghandhi´s philosophy that he decided not only to change his life according to Ruskin´s teaching, but also to publish his own newspaper, from a farm where everybody would get the same salary, without distinction of function, race, or nationality.

Unto This Last was translated into Chinese in 2011 as 给这最后来的 (Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press).

A well-known Chinese tale tells the story of a group of blind men who were arguing about what an elephant looked like. As nobody could convince the others, they asked that an elephant be brought before them. The first blind man, who touched the animal’s leg, said:

“An elephant is like a column.”

The next placed his hands on the trunk.

“An elephant is like a wall,” he pronounced.

The third, who happened upon the tail, said the animal was like a serpent.

The argument continued. Finally, the man who had brought the elephant described it fully, ending all discussion.

Much of what we think, and share with the world, is determined by our own shortfalls, prejudices, and limited vision. Raymond Dawson, the British academic who dedicated his life to studying and writing about China, observes in his book The Dragon is a Chameleon that, “Our response to China is conditioned in part by the objective situation that already exists there, and in part by the conscious and unconscious interests of our own education.”

Time ago in a radio interview, Spanish science commentator Eduardo Punset summed up the function of the brain as being little more than helping us to avoid bumping into things. His view questions our conceited overestimation of the products of our intellect, what we call ideas and opinions. Punset argues that the source of the avalanche of stimuli that constantly bombards our brain is simply our ever-diminishing senses: we see little, hear less, and our sense of smell isn’t much use unless applied to odors that emanate from the immediate space around us. As for touch and taste, it is probably wiser to avoid comment. The key question we have to address is how does the brain order that avalanche of stimuli into something we can more or less make sense of, and that we can then label “rational”—arguably the most pompous of terms. It would seem wiser therefore to avoid pretentiousness and accept that our head has fulfilled its purpose by allowing us to avoid knocking into the side table in the hall, which is no small matter.

News about China, whether in the Spanish or international media, is always framed in terms of the great yellow power, the birth of a global giant, the return of the empire, etc. And while it is true that a lot of China reporting addresses the huge political and economic challenges the country will face in the coming decades, in general, the message is one of an new world power; the birth of a dragon that will burn anything that tries to stop it to a crisp.

But a glance through the pages of history shows that the West’s perceptions of this dragon have changed according to the needs and views of each age. In 1245, fear of the Mongol Hordes prompted Pope Innocent IV to task Franciscan monk John of Plano Carpini to spy on the court of the Great Khan under the pretext of exploring the possibilities of Christianizing the Mongols. The most famous explorer of that age was of course Marco Polo, sometimes dubbed Il Milione for his tendency to stick several zeros on any figure he cited. Polo and Plano Carpini, as did the explorers who followed in their steps in the following two centuries, made constant reference in their writings of the immense wealth of the East, a veritable horn of plenty. They were doubtless influenced by Genesis 2.8: “And the LORD God planted a garden eastward in Eden”. The Orient has always exercised a fascination over the West’s collective imagination.

By the sixteenth century, when the opening of sea routes meant it was no longer necessary to trek overland, carting bags of precious stones to pay for the journey, our view of China changed: we were no longer dazzled by its treasures; and we began to form a different image of China.

It would be the Jesuits, at least until the order was abolished in 1773, who would be the world’s opinion makers regarding China. The Jesuits only contact would be through the emperor and his cadre of elite civil servants the mandarins: after all, their goal was to evangelize the country downwards. The Jesuits, inspired by Plato’s Republic, portrayed China in utopian terms. The intellectual elite of Europe, they dreamed of a government composed of philosophers, and saw China as the model to follow. But were they right to depict the China of the mandarins as a utopia?

When Dawson describes China as a chameleon he is referring directly to the China that changes depending on the magnifying glass through which it is observed. Aren’t the astonishing growth statistics, the incredible rags to riches tales, and the awe China inspires simply the other side of the coin in terms of the West’s development, a West as much in need of cheap labor as a new spiritual reserve?

The cost of creating the West’s so-called welfare state has been high; what will be the cost of China’s wellbeing? One thing we can rely on is that nobody will come along to explain to us what an elephant looks like.