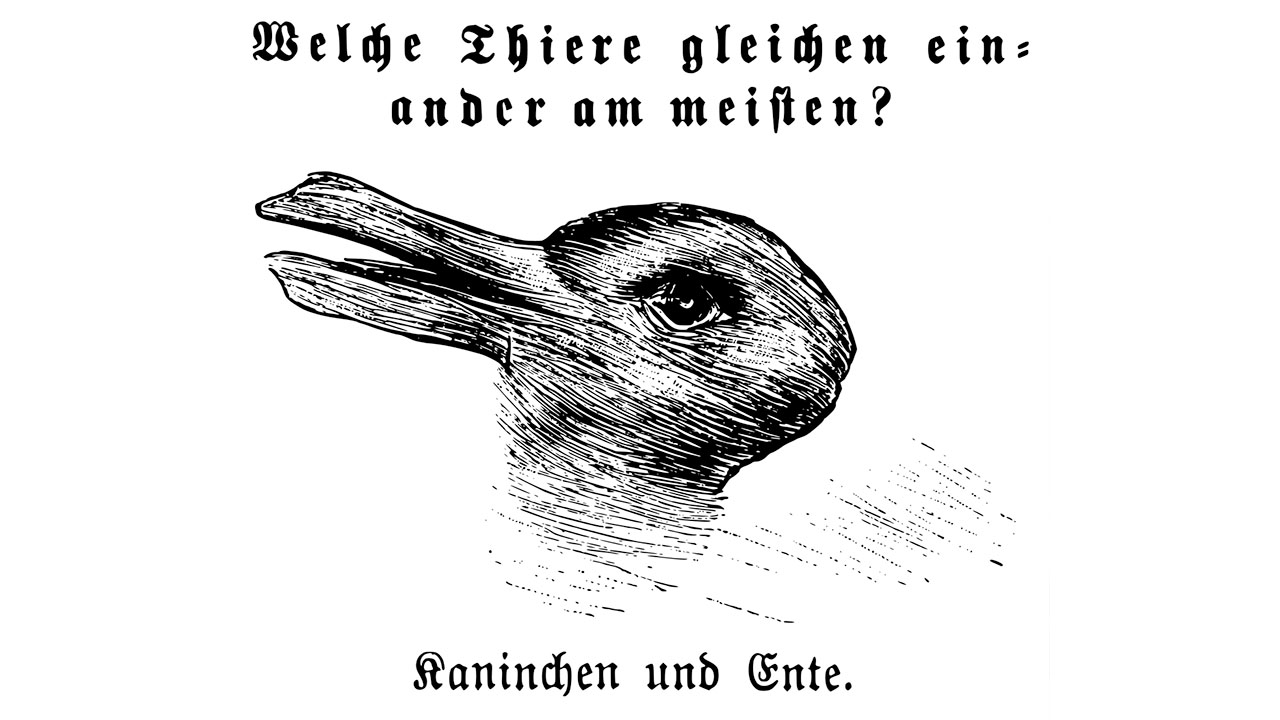

We can’t avoid acting in accordance with plans, after all, a plan provides security and reduces our degree of uncertainty to tolerable levels. That said, it’s also nice to forget the plan and allow life to surprise us, because a surprise can often give us that vital hit we were hoping for or simply lift us out of our planned boredom.

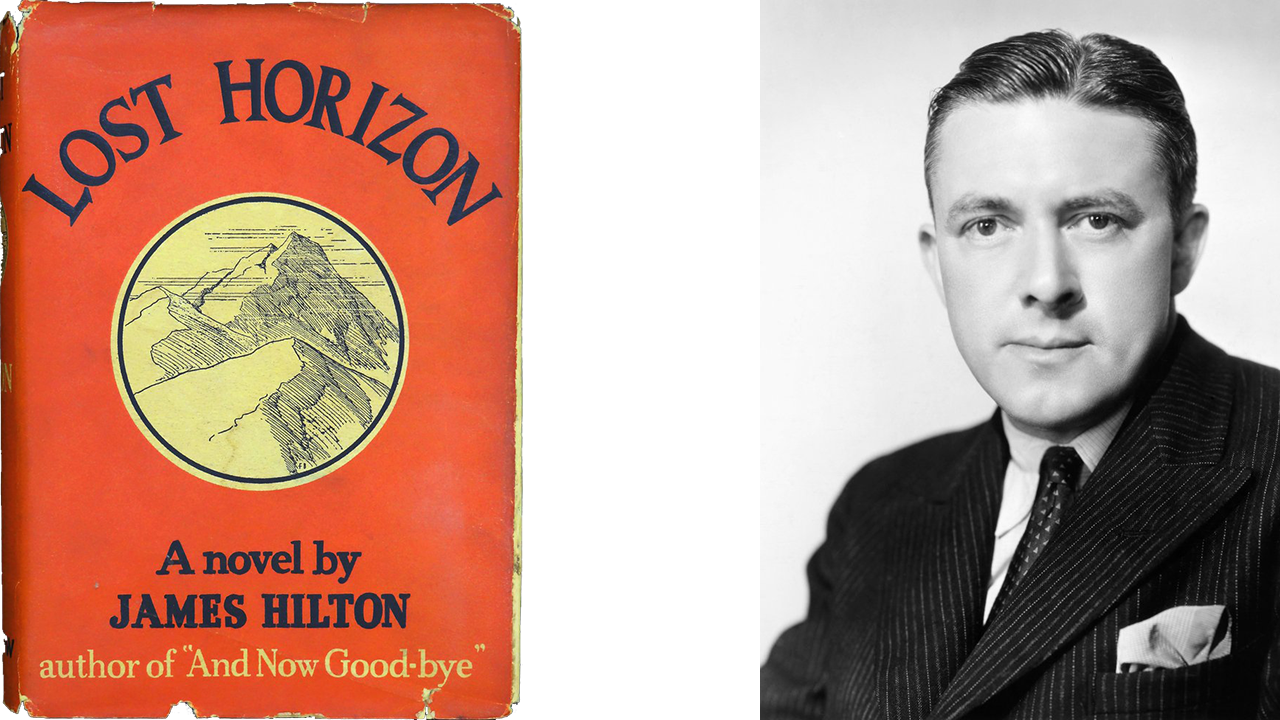

I say this because flying between Beijing and Shanghai last week, I picked up a copy of the China Daily and half-heartedly began to scan its pages. When I opened it, I came across a great article called Where is Shangri-La? by Simon Chapman and DJ Clark about one of my favorite books, Lost Horizon, by the writer and prolific smoker James Hilton, who was born in 1900 and died at the early age of 54.

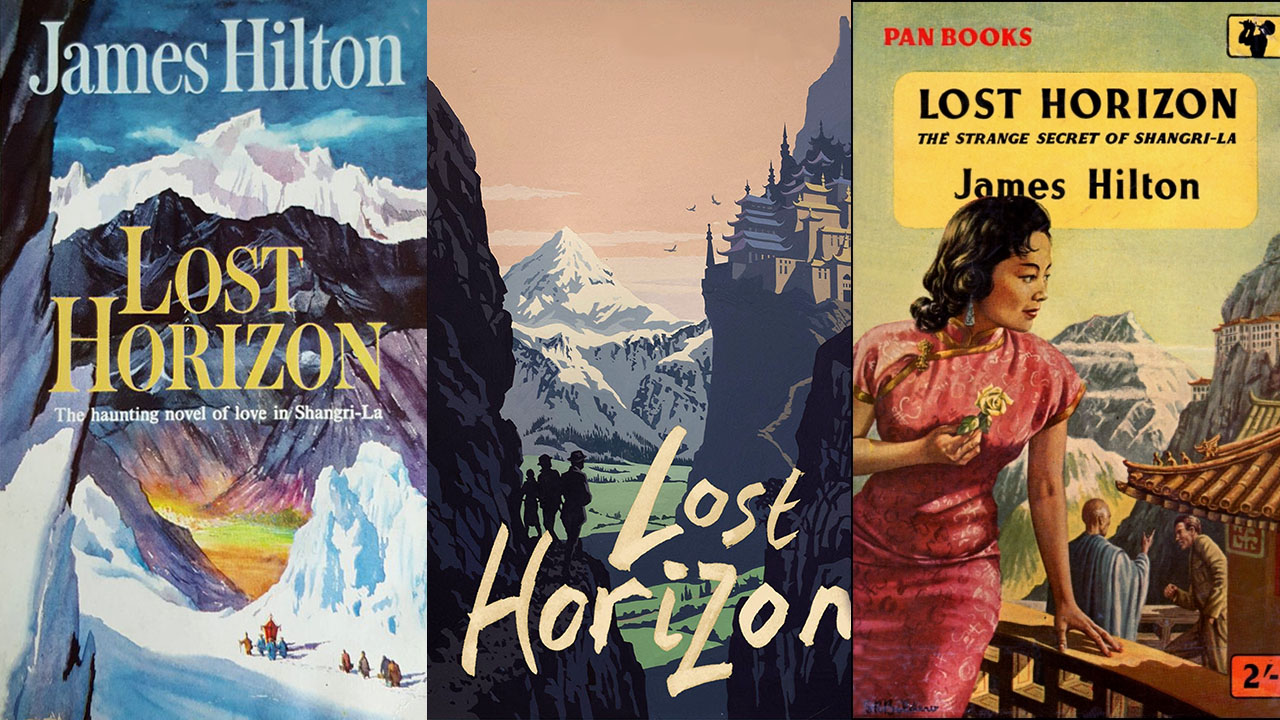

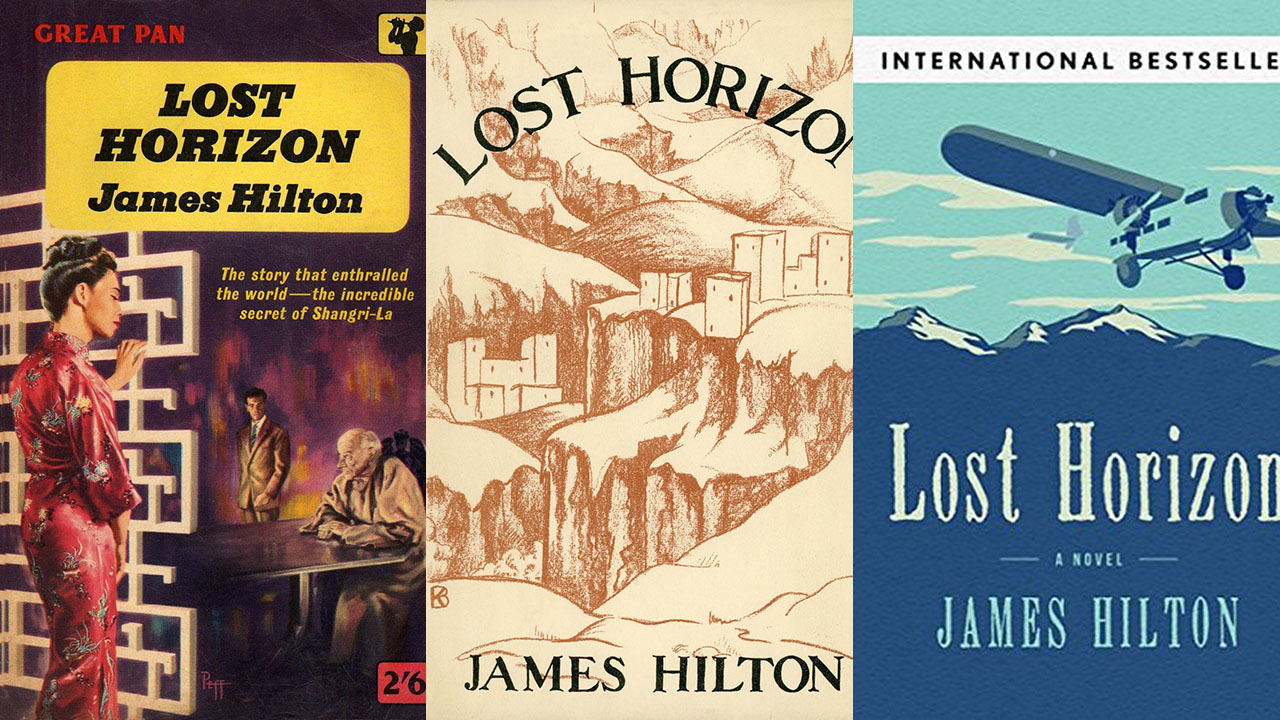

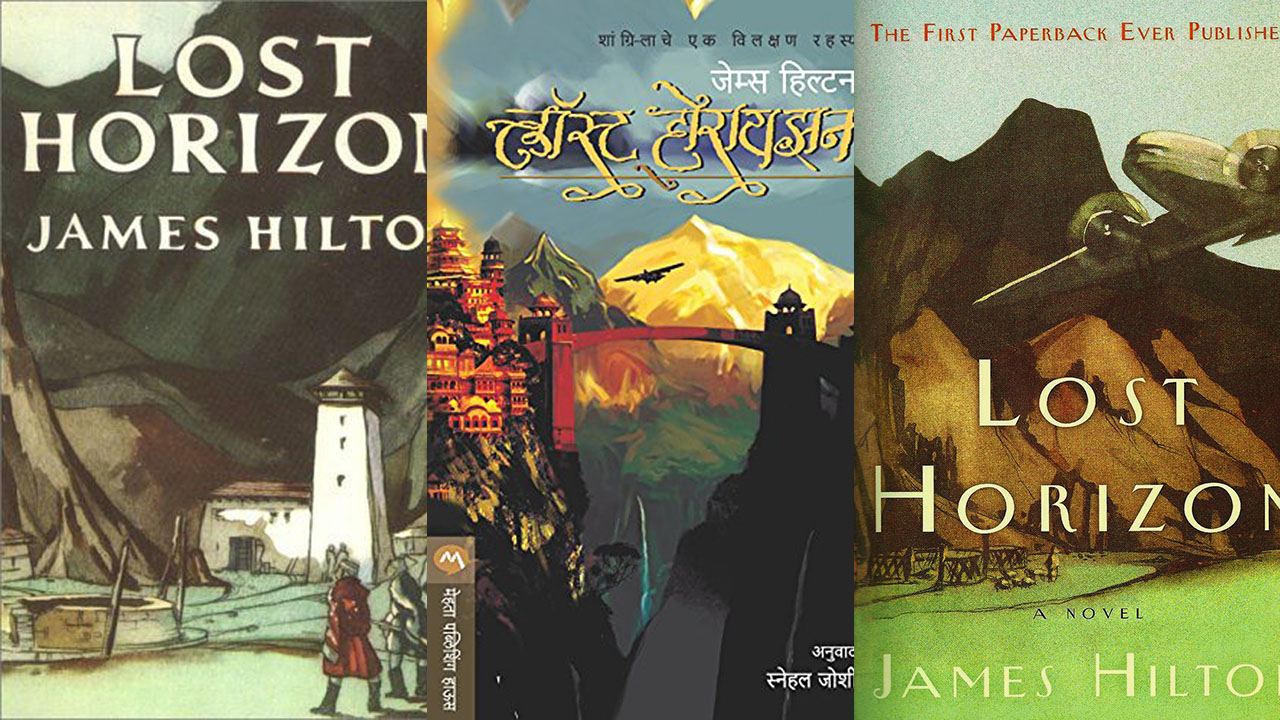

Needless to say, Lost Horizon, published in 1933 and an immediate international best-seller, is the origin of the term Shangri-La, a fictional Tibetan utopia that has not only captured the western imagination, along with other mythical places such as El Dorado and Xanadu, but also lends its name to an international hotel chain. Any number of communities have claimed to be the origin of the paradise Hilton invented (incidentally, he never visited the region), among them, Lijiang, Zhongdian, both in China’s Yunnan province. Shangri-La in Chinese is written 香格里拉 (Xianggelila).

Chapman and Clark focus on the question of why Hilton never admitted that the earthly paradise in his book was based on a series of articles written by the Austrian Joseph Rock published in the National Geographic, while accepting the lesser influence of Father Évariste Régis Huc.

I’ll leave you with the beginning of the novel, as said, one of my favorites, which is nothing more nor less than a great story well told: “Cigars had burned low, and we were beginning to sample the disillusionment that usually afflicts old school friends who have met again as men and found themselves with less in common than they had believed they had…

A triangulated head is clearly a mystery, because the number three has always been a mystery.

A triangulated head is clearly a mystery, because the number three has always been a mystery.

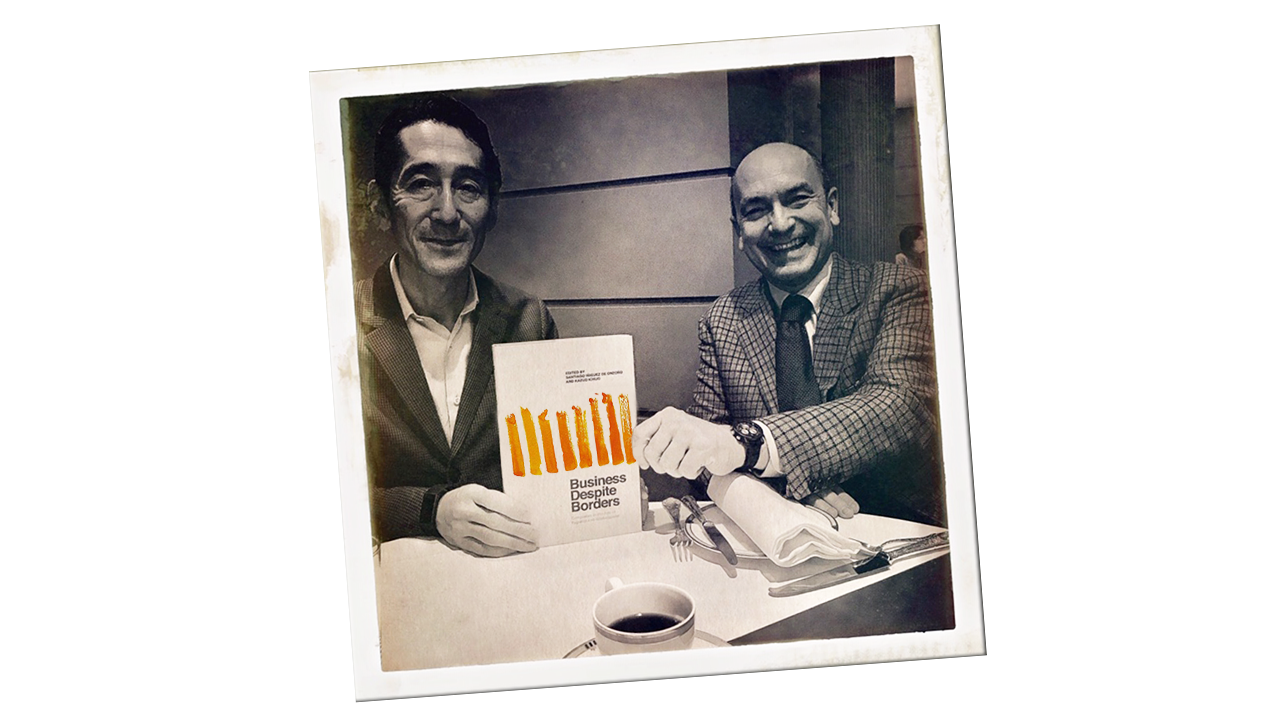

P.S.: Other books by Iniguez are

P.S.: Other books by Iniguez are