As you know, the Chinese Zodiac, also known as Sheng Xiao (生肖), is based on a twelve-year cycle. Each year in that cycle is related to an animal sign. These signs are the rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog and finally, the pig. AIl is calculated according to the Chinese lunar calendar. Since this coming year is the year of the pig, we all have to find out what is the relationship of our own animal sign, the snake in my case, with the pig, in order to figure out how our life is gonna be this year. It seems the beneficial pig effect on the serpent will be reflected in my revenues and some good luck in any new ventures I might undertake. Will I strike it lucky? Let’s have a closer look.

I suppose living a life can be compared to writing a novel. In theory, we have a whole life ahead of us: a pile of blank pages we can fill with words. People who write novels or who live supposedly successful lives always say how easy it is: it’s just a question of getting down to it. They give the impression they’re always headed in the right direction and that everything they do has, or had, a goal or a purpose to it. Does the pig, or any of the other Chinese Zodiac animals, give a hand to them?

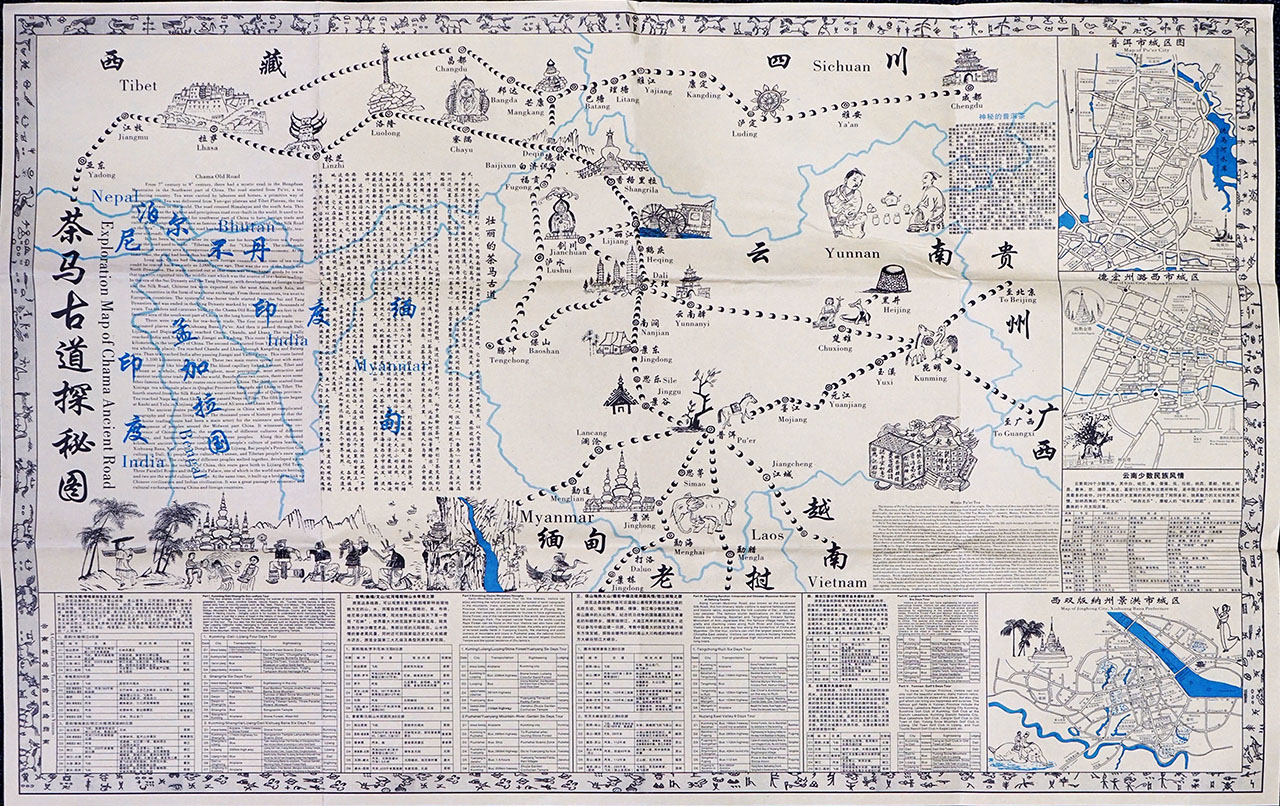

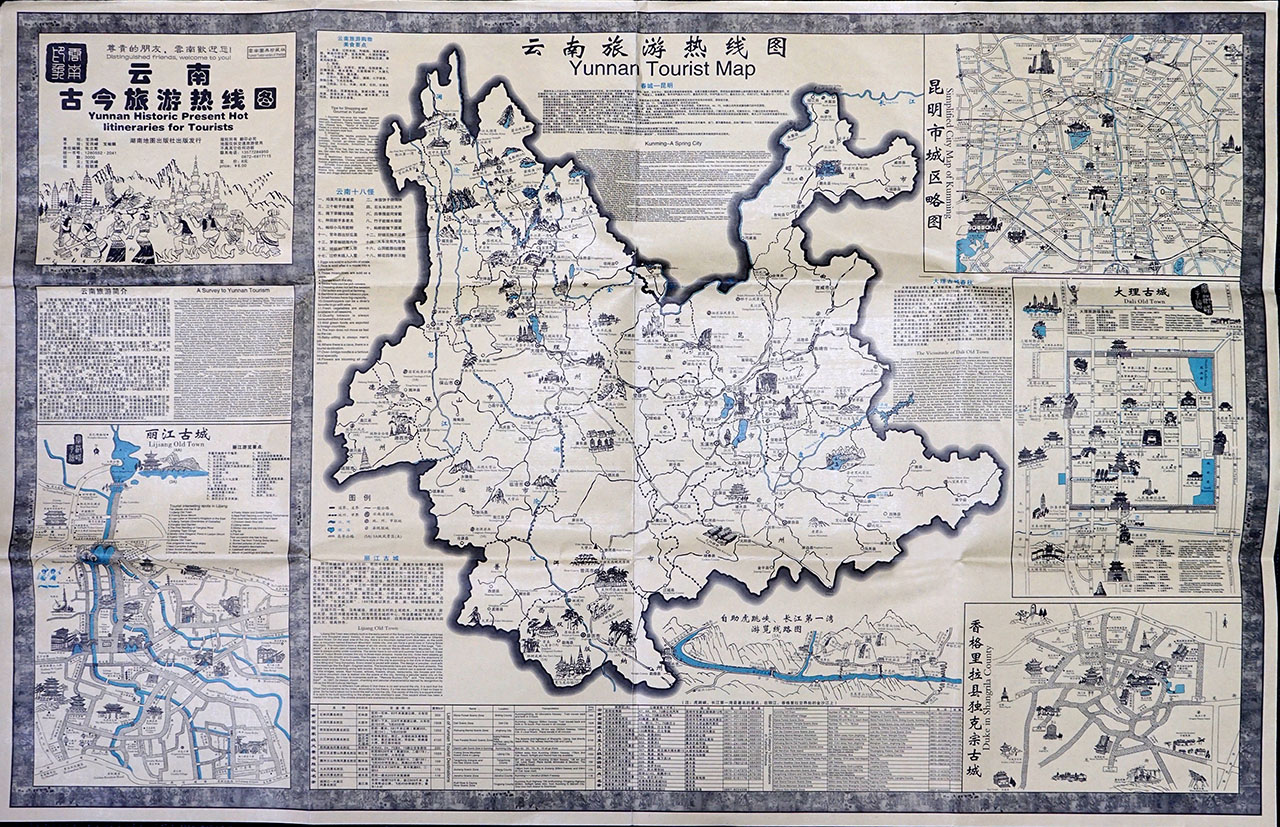

In contrast, I have to confess that I have a terrible sense of direction, and whenever I go somewhere, be it on foot, by motorbike, or by plane, I always think I am headed north, i.e. in the right direction, even though I might be going south. I really have tried to get my head round this, but with little success. I was born in Brussels to a mother from the Canary Islands and an Ecuadorian father, so I did wonder if my family’s ‘Southern Roots’ had disorientated me to the extent that I didn’t even know where the centre was any more. That’s the way things are; I’m not going to go into why I prefer the north because of my complex about the south, or because it’s more developed, or whatever… I doubt the pig can give me any directions!

If each place is its own centre, the same goes for each life, and the same goes for maps; their centre is relative: it depends on the country where you buy them. If you are in China, the centre of the map branches out from there, and if you are in Mali, the same principle more or less applies. In point of fact, when we examine our lives and place in the great scheme of things ours is the perspective of a mosquito. When we talk about life, and not some auto-life, what do we really mean?

Let’s dig a little deeper. I picture a huge GoogleBio focusing on different lives. Like the countries listed on Google Earth, when our lives are seen from the perspective of a roll call, they all look the same; any differences are simply details. These details may be important for those concerned, but they are so trivial, so tiny; barely changing our mosquito’s perspective, that without wanting to, we come up against the limits of existence; with that unbearable lightness of being.

I’m saying this because there is something unreal about this vivre à l’essai, this putting our lives to the test all the time: we can do something, or do the complete opposite without it affecting our existence one iota. ‘Can’t we do anything right (1)?’ , Goethe once asked. Well, I’m afraid we can’t. We don’t do anything right, and worse still, we have very little room for manoeuvre. What ill luck we have, my dear pig!!!

Some Details

It might seem trivial, but the day I was given my Chinese name was a momentous occasion. Not so much for the event itself, when I didn’t really take it in, but for the significance it took on later. Things still existed, even before they had a name, but they were somehow different; I would say their existence was diminished. So, when they called me Táng Mènglóng (唐梦龙), I somehow felt that I had acquired a complete existence again, perhaps because this baptism created another way of existing in the world, and possibly reflected how I had changed over the years. Maybe it wasn’t even that: perhaps it merely confirmed what I had always been. It’s at this point where I begin to have doubts, and, going back to the subject in question, I’m never sure about the extent to which our decisions make any differences to our lives. Probably none.

Due to the peculiarity of Chinese writing, and also the fact that the language is replete with homophonic words, the characters chosen for names are vitally important. A good example is the word 梦 (meng: to dream) which can be spelt (meng): meaning ‘the first month in a season’. It also means ‘older brother’, but more importantly, it is also the first character of the name of the 4th-3rd century BCE Confusian philosopher Mencius (孟子 Mengzi) . The fact my teacher chose a character which refers to a dream world imbues my name with an oneiric, idealistic nuance, which it wouldn’t have otherwise.

Moreover, this character 唐 (Táng), which would be my new surname, also connotes the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), considered the most glorious period of Chinese rule. The third carácter 龙 (Lóng) means ‘dragon’, which is one of the symbols of China. This, coupled with the fact that these three characters in Chinese phonetics sound good together, means that when I say my name I am often complimented, given that I am the dragon which dreams of the Tang dynasty. At the same time, the name also conjures up the Ming dynasty writer Feng Menglong (冯梦龙), who lived between 1574 and 1645.

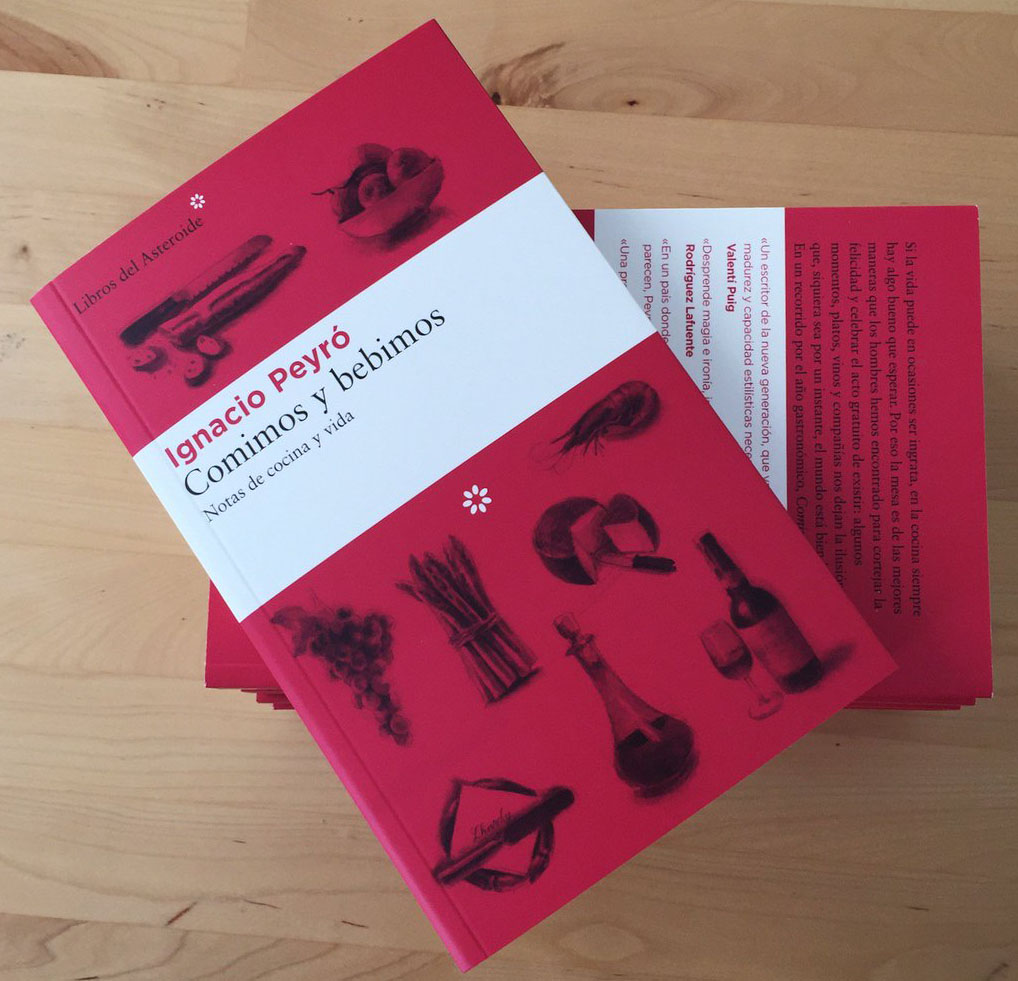

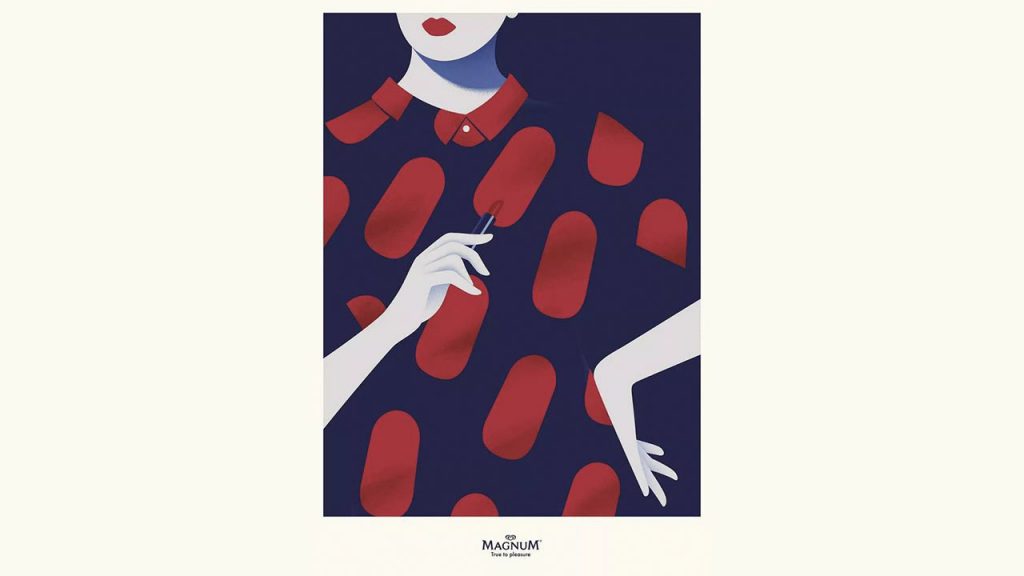

That said, an ice cream called Menglong (梦龙) has become popular in China, as a result of which people are increasingly likely to say “Ah, like the ice cream!” when I tell them my name. I can’t do anything about it. If you look at the photo, you can see the problem.

Spanish friends say my Chinese name Menglong sounds like the word “melón“, and I suppose at the end of the day, that’s what it boils down to. “A bit like a melon” means a “bit nutty” in Spanish, and that’s not far from the truth. Needless to say, that wasn’t how I imagined things would turn out. C’est la vie. Dear pig, can you still give me a hand?

(1) “Sage, tun wir nicht recht?” is Goethe’s original quote.